The Doklam Logjam: India Takes on Chinese Incursion in Bhutan

File photo taken on July 10, 2008 – A Chinese soldier gestures as he stands near an Indian soldier on the Chinese side of the ancient Nathu La border crossing between India and China. When the two Asian giants opened the 4,500-meter-high (15,000 feet) pass in 2006 to improve ties dogged by a bitter war in 1962 that saw the route closed for 44 years, many on both sides hoped it would boost trade. Two years on, optimism has given way to despair as the flow of traders has shrunk to a trickle because of red tape, poor facilities and sub-standard roads. (Diptendu Dutta/AFP/Getty Images)

India will stay “firm and resolute” both at the ground or military level at Doklam in the Bhutanese territory while keeping all diplomatic channels open to scale down tensions with its belligerent neighbor, China. This is in line with the 2012 accord that mandated both countries to designate two special representatives to finalize on the tri-junction boundary points in consultation with another neighbor Bhutan. Doklam area has been a bone of contention for both Chinese and Bhutanese as the 269 square kilometers of narrow plateau lies in the tri-junction region of Bhutan, China and India, near to the modern day Yadong county of Tibetan Autonomous Region and the Ha valley of Bhutan, writes Priyanka Bhardwaj.

Strategically, the disputed territory is located not more than 15 kilometers southeast of the Nathu La pass that separates India and China, and its western edge connects Sikkim to Tibet, and is therefore very significant to India from its defense point of view.

However, in complete and unilateral violation of the 2012, and even 1988 and 1998 agreements between Bhutan and China to maintain peace and status quo in the region till the final resolution is reached between the two countries, Beijing’s Liberation Army has recently attempted to needlessly and in an unprovoked fashion “bully” Bhutan and its media unleashing a barrage of anti-India statements on a daily basis as New Delhi has come out in full support to protect Bhutan’s sovereignty and security, while posturing to adopt a politico-diplomatic reasonability to sort out the troop stand-off.

The Bhutanese demarche to China against its incursion having yielded nothing at all. New Delhi has responded by steadily adopting an “enhanced border management posture” with deployment of additional acclimatized soldiers as the area near the Sikkim-Bhutan-Tibet tri-junction is 11,000 feet above sea level and preparation of contingency plans.

Apart from the already stationed 63 and 112 Brigades (over 3,000 troops each) in East and North-East Sikkim, Indian Army has moved up another 2,500 soldiers from the 164 Brigade to Zuluk and Nathang Valley in the state to further reinforce its military stance.

Doing the rounds of social networking sites the scene at the face off site reveals 300-400 soldiers from both sides showing red-flags to each other in a “non-aggressive” manner.

This 2017 issue began when Chinese soldiers entered Doklam, pushed aside Bhutanese soldiers and constructed a road in the area that was physically blocked by Indian troops in mid-June.

Despite India’s repeated calls to Beijing to withdraw troops and come to the table for talks China has retaliated with counters that New Delhi must de-escalate from the area and not try to “push its luck.”

Since India’s asylum to the fleeing Buddhist spiritual leader, Dalai Lama, in 1959 and permission to allow a Tibetan Government in exile to operate from Dharamsala, and the 1962 Indo-Chinese bloody war when China seized control of some Indian territory, both countries regularly patrol unmarked territories.

Besides, the Chinese have also staked wrong claims to many Himalayan areas, 90,000 square kilometers in Arunachal Pradesh, referred to as “Southern Tibet” by Chinese, and 38,000 sq.km of the plateau of Aksai Chin.

Hence viewing China as an enemy of all seasons and with the escalation of tensions the Indian security establishment has been put on high alert in the event of an all military conflict and the event of major units of the Chinese army marching southwards, across the 11 bridges on the Tsangpo river.

While there has been widespread support for India’s hard line yet restrained stance and far more measured rhetoric in the international arena, none whatsoever has come for China for its aggression of a weaker nation over a very minor issue, though its peculiar friendship with Pakistan has all along witnessed the latter buttressing Beijing’s intentions with a continuous shelling of schools at its borders with India and engaging in a low intensity war rather than a full-scale war.

Considering India’s strong relations with Thimpu, the Bhutanese call for help, and absence of diplomatic ties between Bhutan and China, there are expectations of forward movements to be initiated by New Delhi.

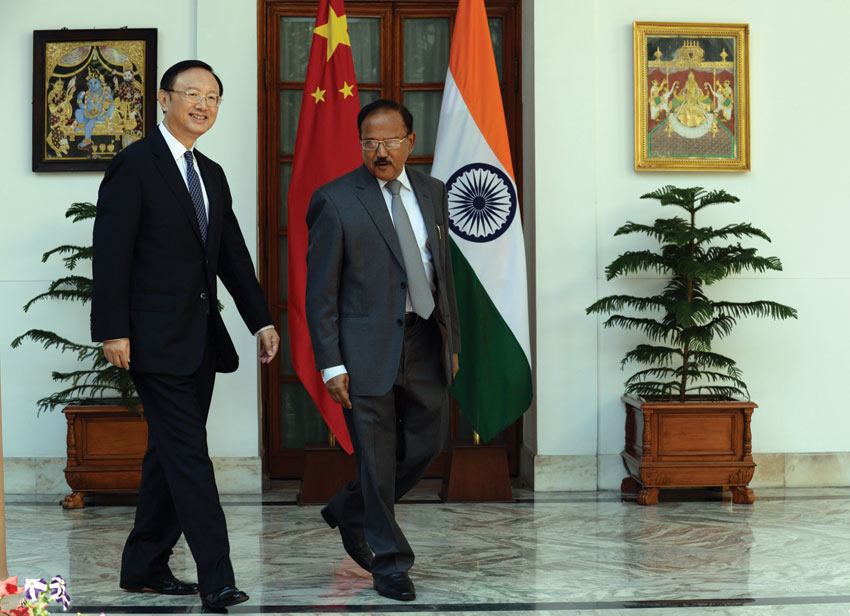

When India’s National Security Advisor Ajit Doval attends the meeting of NSAs from BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries in Beijing on July 27-28, both sides feel that some understanding on a probable withdrawal of rival troops from the military stand-off site may be on the cards.

The again in September the BRICS (five-member bloc of emerging countries) Summit will see the attendance of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Writing in The Global Times, a Communist Party of China mouthpiece and one which has been recently airing views of the Chinese state, a research fellow at the China Reform Forum think tank, Ma Jiali said, “Doval’s visit would serve as an opportunity to ease India-China tensions…China would lodge solemn representation with the Indian side during Doval’s visit, hoping it could take measures to ease the tension. India may make some requests as a bargaining chip for its pulling out troops.”

And failure of an agreement on the contrary would deteriorate ties he warned.

Indian analysts, however, see every Chinese move as part of a larger hegemonic power game that it embarked up post 2008 financial crisis, of which its presence in Doklam following its dominance along the Indian borders at Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh, and vigorous wooing of Bhutan and other smaller countries in India’s traditional sphere of influence, including Nepal, Sri Lanka and Myanmar and the several billions of dollars worth of CPEC are just a part of.

It is quite possible that India’s resoluteness has taken the Chinese by surprise and this approach may earn flexibility and favor in negotiations for India when Beijing sits and talks, and this will happen only when Beijing is sure it will lose more by prolonging or escalating the crisis.

Meanwhile, New Delhi will need to bear caution that the presence of its troops on Bhutanese soil does not cause much consternation in the Bhutanese population or lead to sequels of neighboring countries seeking third party interventions in future territorial disputes, namely the Chinese presence in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.