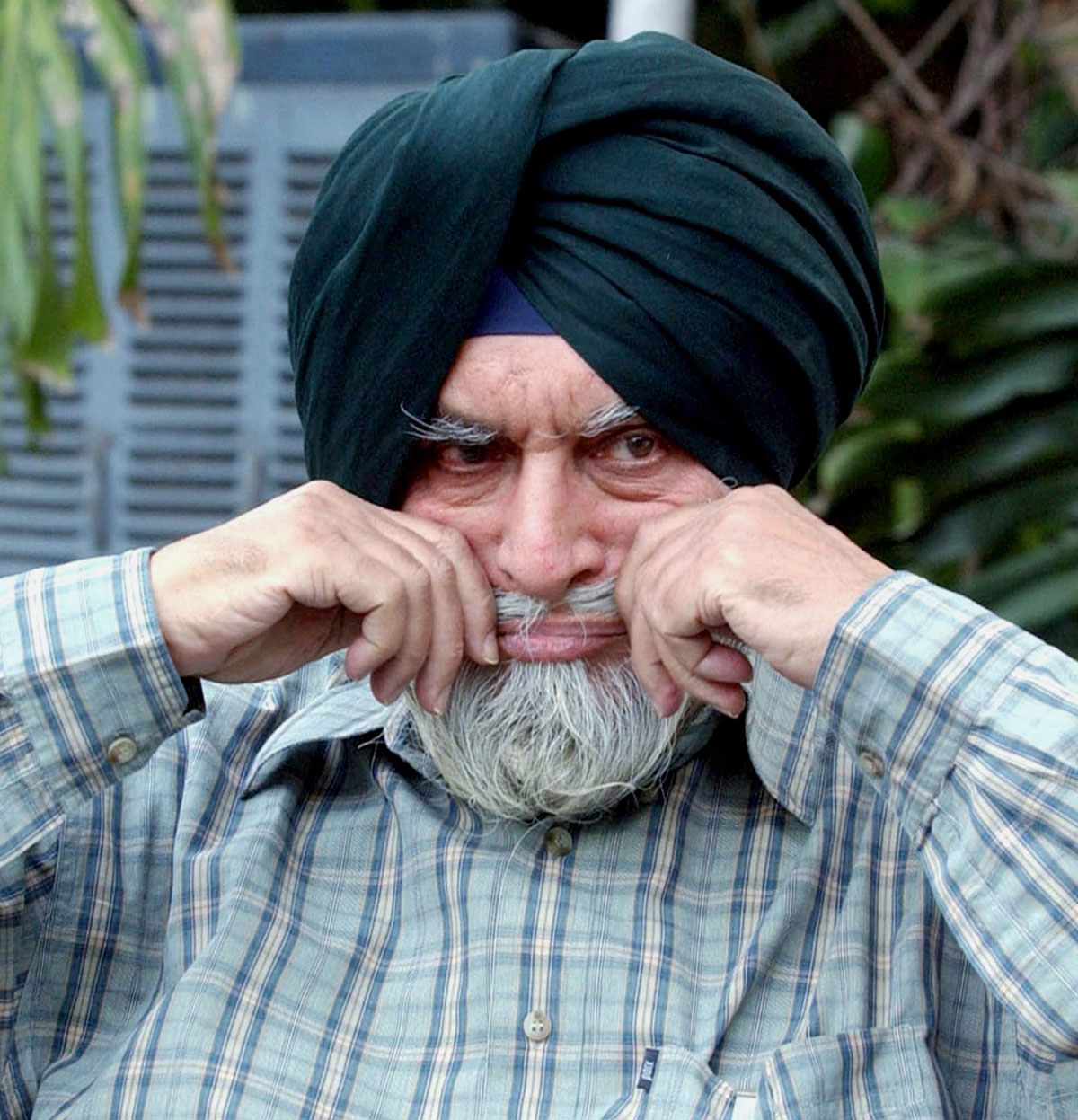

Super Cop ‘Lion Man’ of Punjab, K.P.S. Gill Passes Away

File photo of former Punjab DGP K.P.S. Gill who passed away at a hospital in New Delhi, May 26. He was 82. (Vijay Kumar Joshi/PTI)

Kanwar Pal Singh Gill, one of India’s most celebrated police officers, passed away, May 26, in New Delhi. Born in 1934 he was selected to the Assam and Meghalaya states’ (in North East India) cadre of the most competitive and elite Indian Police Service (IPS), and went on to become the Director General of Police (DGP) for Assam till 1984 and then Punjab till 1995. Priyanka Bhardwaj pays tribute to K.P.S. Gill.

Even after retirement from active police service the indomitable, 6’ 3’’ tall and gruff man with a gentleman’s demeanor engaged in forming the Indian Hockey Federation under the aegis of Indian Olympic Association, founding and heading the Institute for Conflict Management besides writing books on his experiences, editing, public-speaking, consulting on counter-terrorism and indulging in frequent and erudite English poetic and Urdu Shairi exchanges.

What makes Gill stand apart was his fearless attitude due to which regardless of any threat to his personal or family’s safety he successfully brought an end to Sikh terrorism in Punjab.

Known for his criticism of soft nature, unpreparedness and lack of a national security policy on part of the Indian Government in handling of national security issues, his thrust was on toughness and preparedness.

On his main role as the head of the Assam police force Gill who had earned for himself the title of “super cop” in Punjab had already tasted controversy for acting against illegal migration in Assam in early 1980s.

In the 1980s, the Khalistan movement had reached such dangerous levels that several bureaucrats in private circles would speculate on an “imminent separation of Punjab from India!”

For two terms, from 1984-1995 he led the Punjab police to handle this insurgency that had clearly gone out of hand.

The Sikh terrorists with the tacit support of Pakistan who by then had substituted their direct attacks on India with the silent war of a “thousand cuts” had propped up the Khalistan movement that demanded an independence of land of the Sikhs from India and had in the process bent down to selective assassination of Hindus or whoever opposed their goal.

Thousands of Hindus fled their ancestral land and even the Punjab capital of Chandigarh to Haryana, Delhi or Hindu-majority areas in neighboring states for fear of their lives.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s 1984 Operation Blue Star conducted by the army had back-fired back and she was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards and this led to severe anti-Sikh riots in Northern cities as thousands were killed, burnt alive or injured.

The central government was intent on exterminating terrorism from Punjab and Gill, himself a Sikh, was deputed to lead the government’s goal of a successful resolution.

In the super cop’s own words, the police plan remained the same as before but with new elements added to the strategy.

Gradually over the years the mission was accomplished.

The first time ever a media was invited by police forces to cover live a major anti-terrorist operation being conducted with the least casualties or possible damage to the sacred Golden Temple where the terrorists were holed up in the May of 1988.

This was the successful Operation Black Thunder that yielded in the arrest of about 67 militants and killing of 43 more.

The entire nation was glued to their television sets watching with bated breath as militant after militant was killed or captured and the recovery of drugs, arms, ammunition, filth and even women kept by these militants from the sanctum sanctorum of the holy shrine.

As the cop himself conceded on many occasions, brute force was used as it was the only way to eliminate and not merely arrest militants, their ideological leaders and assortment of supporters, who reigned terror in the entire state that once flourished under the Green Revolution.

A shrewd officer, Gill pitted Jat (a peasant community that now owns land and practices agriculture) police officers and informers against the militants who were almost wholly from that community.

Once when questioned on his counter-terror tactics, Gill assiduously brushed it aside with a remark, “It is a fight of Jat Sikhs versus Jat militants.”

Those who fulfilled the Gill’s task were handsomely awarded, bounties were announced on heads of terrorists, ample resources were deployed to settle witnesses in far off locations and low rank officers were promoted to higher levels on basis of “merit” and with no interference of bureaucratic assessments.

A sum of approximately Rs. 50,000 ($1,670, now less than $1,000) was a usual reward for killing or arrest of a listed militant in 1992.

The annual outlay of rewards was to the tune of the tune of Rs 0.01 billion ($338, 000) in the early 1990s

This led to a “rush to claim cash rewards” which perhaps could also have led to a few policemen acting as “mercenaries” if left unchecked and also to the “residual criminality” that seeps to higher levels in Gill’s own words.

But the chief cop protected his force against all allegations of human rights violations that was raised by especially those who had been supporters of the activities and ideologies of Khalistanis and had escaped to the Americas particularly Canada via asylum routes.

Though most of the allegations had been squashed by the judiciary a few cases are still pending unresolved.

However, it was the case of assassination of human rights activist, Jaswant Singh Khalra after he was taken into custody by Punjab Police on Sept. 6, 1995, that created a major controversy for Gill.

Apart from this a blemish to Gill’s checkered career was in the form of the 1996 conviction for sexual harassment of a lady Indian Administrative Service officer at a 1988 party, though whispers in the power corridors weave stories of a conspiracy by detractors and “dislikers,” and then there are charges of “autocratic functioning” of the Hockey association that got mired in corruption, though never of his doing.

Personally the DGP was corruption free and lived within his means, so much so that on his death his step mother informed presspersons that the cop had a mere Rs.150,000 ($2,238) in his personal account.

Post retirement, Chief minister of Assam, Prafulla Kumar Mahanta requested Gill to advise on terror related issues as the state was engulfed in its fight against ULFA and BODO militants, but which could not be accepted by the cop.

In 2000-04 he successfully advised the Sri Lankan government in their counter-terrorism strategy against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and within India Gill was taken on as Gujarat security advisor in the aftermath of Godhra by the then Chief Minister of Gujarat, Narendra Modi.

Once an eminent global speaker had tried to draw global attention to the tactics and strategies of Gill in tackling the Afghan Taliban that continues to rear its ugly head and threaten world security.

There was complete admiration for his successful ideas, energy and zest from all quarters.

Even a few weeks before his demise he had evinced interest in eliminating Maoism from Chhatisgarh state if given the mandate for three years.

But life seems to have had other plans for this down to earth operations guy as he failed to survive the peritonitis that left him gravely weak and ill.

Gill is survived by his wife, two children, stepmother and step siblings and a millions of others who will remember his valor to enable peace and life for all in the beautiful ancient land of Punjab.

For his yeoman service, the Sardar was decorated with a Padma Shri award, the nation’s fourth-highest civilian honor in 1989.

There are always two sides to a story. This man killed many innocent Sikhs and was called the butcher if Punjab. He terrorised families and destroyed a generation through his butchery. Only God can give justice to a man like this. He was a monster!