Democratic Rights to Ensure Development: India Recognizes Privacy as a Fundamental Right

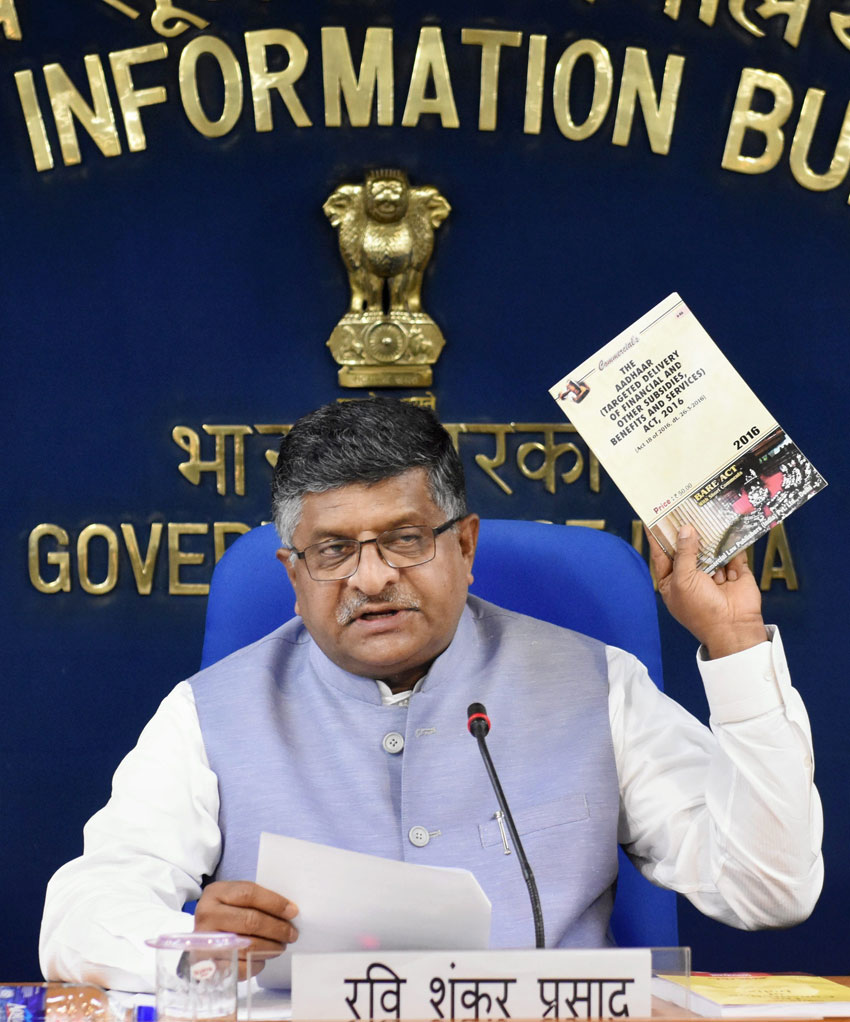

Union Minister of Electronics & Information Technology and Law & Justice, Ravi Shankar Prasad during a press conference on Supreme Court’s ruling on Right to Privacy, at Shastri Bhavan in New Delhi, Aug. 24. (Subhav Shukla/PTI)

August 2017 will go down in history as the month of constitutional victories for India and its citizens and may be hailed as a fresh beginning in the constitutional jurisprudence of the country. The 24th day of the month saw a landmark verdict in the declaration of Right to Privacy, one which inheres in every human personality, as a human right and therefore a fundamental right that mandates constitutional protection, writes Priyanka Bhardwaj.

The nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court that unanimously upheld the right to privacy after 67 years of the Indian Constitution into commencement in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retired) versus Union of India case comprised of Justices Khehar, J. Chelameswar, S.A. Bobde, R.K. Agrawal, R.F. Nariman, A.M. Sapre, D.Y. Chandrachud, Sanjay K. Kaul and S. Abdul Nazeer.

The judgment, as it stands, holds that the right to privacy stems from the guarantee of life and personal liberty in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, and in different contexts translates into other facets of freedom and dignity as is recognized and guaranteed by the Fundamental Rights contained in Part III of the Constitution.

The significance of this right lies in that it can neither be curtailed nor abrogated by a statute in the absence of a constitutional amendment subject to specific constitutional prerequisites.

To ensure clarity in any attempts of dilution of any right in Article 21 in future, the three-pronged test vested in legality, objectivity and proportionality has been adopted.

Moreover, since the right to privacy may not be infallible, the ruling provides for reconsideration and overruling of past judgments, only if they are found to be erroneous and not conducive to the protection and promotion of fundamental right.

Hence, the previous eight-judge bench judgment in the M.P. Sharma case, and a six-judge bench judgment in Kharak Singh case, both of which sought to define privacy as a common right and not a fundamental one, may be considered overruled.

Interestingly, this is the first instance of a son’s ruling overruling a father’s previous judgment.

This 547-page judgment of which 266 were written by Justice D.Y. Chandrachud overrules the previous judgment by his own father, longest serving Chief Justice of India Y.V. Chandrachud, who as a Supreme Court judge during Emergency years (1976) had ruled in the much-debated ADM Jabalpur versus Shivakant Shukla case that personal liberty guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution could not go against an executive order.

The redefining of this right to privacy also translates into quashing of the Government of India’s contention that since the Right to Privacy is an elitist construct it may destroy the purpose of welfare schemes for the majority of the population, but rather holds civic and political rights and socio-economic rights as complementary and not mutually exclusive.

In fact, the poorest of the poor needs fundamental rights, including the right to liberty and privacy, to get the government to deliver social and economic welfare the ruling stressed.

The idea of constitutionalism provides for guarantees against the absolutist powers of the state or majoritarian rule, and since traditionally civic and political rights are considered to be negative rights, the judgment seeks to place the right to privacy within the ambit of the fundamental right to life under Article 21, a right of human dignity and consequently reading right to access to basic human needs like food, shelter, health and education.

Representing the opinion of Union of India, the Attorney General, P. Venugopal had argued that in the expression “right to life and personal liberty” in Article 21, “right to life” be given primacy over “right to personal liberty,” since privacy, if at all is a right.

Instead, Justice Chandrachud quoted the writings of Nobel Laureate Professor Amartya Sen in “the Idea of Justice” that the presence of civil and political rights augurs well for the socio-economic rights and abundant examples may be found where stronger democratic societies have handled socio economic crises much better.

To emphasize the link between development and freedom, he also referred to Sen’s “The Country of First Boys” where the author elaborates that the denial of access to basic human needs amounts to denial of “Freedoms” and hence a state of “Unfreedoms” that undeniably causes impediments in the realization of life.

Yet, there also may be typical situations when the right to property, a fundamental right, stands against the establishment of an egalitarian socio-economic regime, and hence it may be also be safe to concur that the primacy of one facet to the other may be unsustainable.

In the current context, the question of privacy enjoying the constitutional status was first raised in several petitions in 2012 when retired High Court Judge K.S. Puttaswamy along with first Chairperson of National Commission for Protection of Child Rights and Magsaysay awardee Shanta Sinha, feminist researcher Kalyani Sen Menon, and many more challenged the previous UPA political dispensation’s decision to introduce the biometric data-enabled Aadhaar ID cards for citizens.

Despite the judgment emphatically stating that the right to privacy is “inalienable” and “inherent” to the most important fundamental right which is the right to liberty, a pre-existing “natural right,” there may be a chance to retrieve the Aadhaar Act if the government reads the right to privacy in this particular context as subservient to the cause of better enabling of access to basic human needs and for good governance.

Perhaps an ordinary legislation in the Parliament may bring in a balance between the right to privacy and objectives of the Aadhaar Act.

This historic decree, apart from reiteration of principles enunciated in the Preamble, is expected to guide disposal of future cases along lines of freedom and liberty and impact daily lives, from online activity to eating habits, and from sexual preferences to welfare scheme benefits.

Equally compelling would be the opening of doors for debates on topics such as scrapping of the archaic Section 377 that criminalizes acts of homosexual union, existential terrorist threats legitimizing government surveillance that would invade and compromise privacy and application of this right to deal with non-state players who hold vast data on private lives of citizens.

Notwithstanding the probable misses of this ruling, the Supreme Court has underlined the fact that it is indeed the sole guardian of the country’s constitution by ensuring a more evolved redefinition of the right to privacy, a subset of natural rights that finds mention in the constitutions of 150 nationalities and has been recognized similarly only by a select league of nations – the United States of America, Canada, South Africa, the European Union, and the UK.