Vaccine Distribution: Behind For Communities of Color

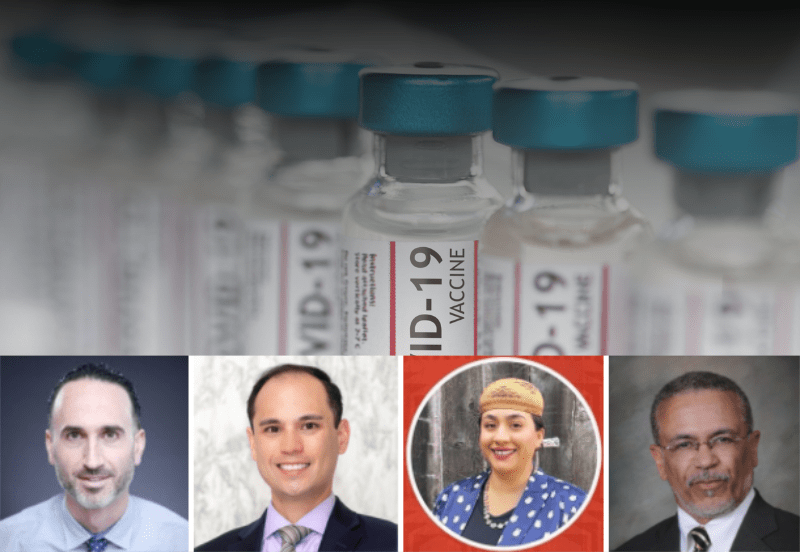

From left to right: Dr. Daniel Turner-Lloveras, Latino Coalition Against COVID-19; Adam Carbullido, Director of Policy and Advocacy at the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations; Virginia Hendrick, Executive Director of the California Consortium for Urban Indian Health; Dr. David M. Carlisle, President and CEO of Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science

People from ethnic communities are dying disproportionately from coronavirus but are not the ones being vaccinated.

By: Jenny Manrique, EMS

Some 55% of COVID-19 fatalities in California are Latino while African-Americans in New York have the highest rates of hospitalization for coronavirus. Yet neither state is reporting racial data about who receives vaccines.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) vaccine monitor, only 23 states in the country share vaccination data by race and ethnicity, and the persistent pattern is that Black and Hispanic people have been vaccinated at very low rates in proportion to infections and deaths from the virus.

“This needs to be immediately corrected,” said Dr. Daniel Turner-Lloveras, founding member of the Latino Coalition against COVID-19 at an Ethnic Media Services press briefing on Feb. 12. “If we are unable to measure and quantify the disparity, it is very difficult to find a solution (to the pandemic).”

According to Turner-Lloveras, the first step to achieving an equitable distribution is to ensure that all states report racial data on who receives the vaccine.

Data analyzed by KFF shows that the largest gaps between states reporting numbers by race are in Delaware where only 6% of those vaccinated are Black, although they account for 24% of the infections. In Louisiana, African Americans have received 13% of vaccinations but suffered from 34% of the infections and in Mississippi 17% of Blacks have been vaccinated but their infection rates reach 38%.

Colorado has vaccinated only 6% of Latinos while Latino infection rates reach 37%; in Oregon only 6% have been vaccinated while 35% have been infected, while inTexas only 16% of have received the vaccine despite representing 43% of cases. The KFF data shows the same vaccination gaps for Native Americans and Asian Americans.

“We need a gigantic digital patient engagement project…with virtual town halls in every neighborhood providing information in the languages people speak,” said the doctor, adding that this is the only way to achieve herd immunity and return to some kind of normalcy.

Long-standing disparities

Disparities in access to healthcare are not new, but COVID-19 has exacerbated them. The health system was unprepared for a pandemic in which ethnic minorities had to resort to underfunded community health centers which are short of beds and acute medical devices.

This is the case at Martin Luther King Hospital in Los Angeles, which needed to call for reinforcements to transfer its most critical COVID patients to other hospitals for oxygenation. All too often, surrounding hospitals refused to receive MLK patients due to lack of insurance.

“MLK staff work 24 hours in the trenches fighting COVID and when they ask for help they are told no repeatedly,” said Dr. David M. Carlisle, president and CEO of the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science.

“This is the hidden face of healthcare. These are the disparities and why people are so concerned about health care … it is unethical and inhumane.”

Carlisle said he is concerned that vaccines are being distributed to commercial pharmacies located in “areas that do not reflect the ethnic diversity” in California such as Huntington Beach, Irvin and Newport Beach while large vaccination centers like the Dodger Stadium run out of doses and have to close. “It is a failure of our public health policy.”

For Virginia Hedrick, executive director of the California Consortium for Urban Indian Health and a member of the Yurok tribe, these disparities show that “we are not all in this together, we are not experiencing it in the same way.”

The data back her up: American Indians and Alaska Natives have contracted COVID at rates three and a half times higher than their white non-Hispanic counterparts. In a given week, they’ve been hospitalized between 4 and 5 times more than whites non-Hispanic. And the death rate overall is 1.8 times higher.

Hedrick said that for Native Americans the pandemic has been a reflection of the “outcomes of historical trauma” to which they have been subjected with the “steal of land, children, language, and culture.” This has resulted in a community suffering from the highest rates of diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, substance abuse and even suicide among the youngest community members.

While the Indian Health Services have a separate vaccine stockpile for both urban Indians and those living on tribal facilities, the doses available in California are not enough for all community members.

Thanks to tribal sovereignty, their tier system has prioritized vulnerable populations with pre-existing conditions regardless of age. If there are young members of the family taking the older ones to get vaccinated, they can receive a vaccine by being recognized as caregivers. But if someone gets sick, there are no Indian Health Service-funded hospitals in California: tribal members rely on a public or private system and insurance.

“We are seeing tribal leaders die, our elders die, and in Indian countries losing an elder is losing knowledge and language that can never be recovered,” Hedrick added.

Resources for the CBOs

Language barriers are also a worry for the indigenous communities of Mexico that make up a large part of the farmworker labor force, and for Asian-Americans who speak up to 50 different languages.

According to Adam Carbullido, director of policy and advocacy at the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations (AAPCHO), Congress should approve more resources for community-based organizations (CBOs) that have been “in the frontline providing care and services when government and private institutions have fallen short ”.

“These clinics need more interpreters and materials translated into different languages,” he observed. “It is important to have providers on hand who can speak the language of (the patient’s) choice not just in a public crisis,” he said.

Carbullido recalled that Asian Americans have the highest risk of hospitalization among any ethnic group and have been subjected to an increase in incidents of hate and xenophobia, “because of the false association of the pandemic with Asians and others who are perceived as foreigners.”

“Patients report fear of seeking health and the care they need… it is a true emotional trauma in Asian American communities and the mental health consequences will have long-standing complications for health,” he concluded.