Journalists in the Cross Hairs: The Dirty War on Information

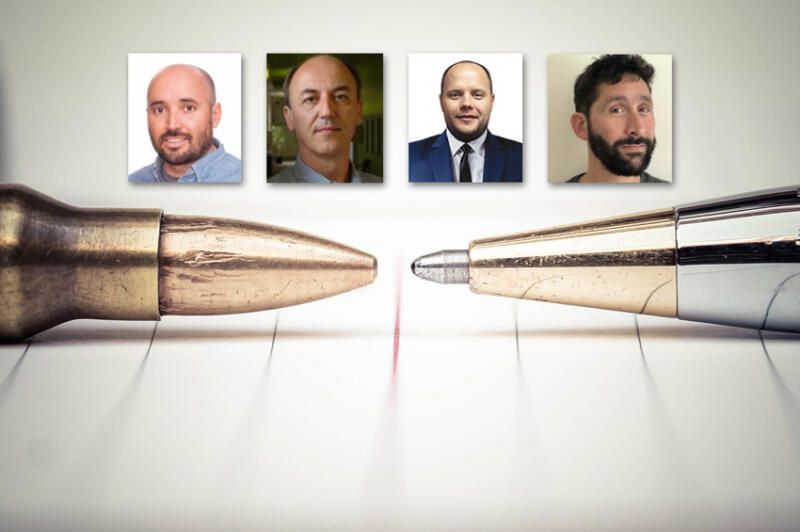

(Above, Inset, l-r): Carlos Martinez de la Serna, Program Director, Committee to Protect Journalists; Ricardo Trotti, Executive Director, Interamerican Press Association (SIP in Spanish); Ruslan Gurzhiy, Editor-in-Chief, SlavicSac, Russian News in California; and Jeremy Goldkorn, Editor-in-Chief, SupChina. (EMS/Siliconeer/Shutterstock)

The global war on information has caught journalists in its crosshairs all over the world. Journalists are being killed, intimidated, harassed, imprisoned, access to the internet and social media is curtailed or reduced in many countries, and social media is full of disinformation and propaganda campaigns. Public opinion about media and journalism is at an all-time low.

“We used to take information for granted. We used to take access to news for granted. Maybe that was the privilege of living in America, but we no longer can do so, it seems, no matter where we live,” said Sandy Close, executive director of Ethnic Media Services.

Speakers – Carlos Martinez de la Serna, Program Director, Committee to Protect Journalists; Ricardo Trotti, Executive Director, Interamerican Press Association (SIP in Spanish); Ruslan Gurzhiy, Editor-in-Chief, SlavicSac, Russian News in California; and Jeremy Goldkorn, Editor-in-Chief, SupChina – discussed these trends at an Ethnic Media Services briefing held April 1.

Carlos Martinez de la Serna provided a very brief overview of how, what’s the state of prison around the world. “Any place where there’s a political crisis, where there’s a crisis of any kind, could be COVID, which is a global health crisis, could be a change in government elections, could be a place where there are protests or demonstrations, or other type of crises like a racial process or others you can think of, information and journalism is also a target so at the same time there’s a war of journalism and information.

“You can think of the years of COVID which are still there though in some places is more relevant than others and governments enacted different laws to stifle journalism to control information.

“During the racial process then the black flight model process in the U.S., there were record numbers of journalists being attacked and imprisoned. The current crisis in eastern Europe, there’s also a war on information.

“Journalists investigating corruption, and political corruption specifically, are the ones usually most targeted because of their work but there are also kind of new trends at the same time, for example last year we documented several dozens of cases, at least 47 jailed journalists on false news charges in 2021 only.

“Most of the cases of killed journalists are never told, so killing a journalist is not usually a problem. Governments know how to not respond for their acts or not how to really do their best for justice to happen in these cases and that’s extremely important as we’ve seen in places like Mexico or others, where there’s a continuous cycle of killing journalists and impunity. A consequence of this global crisis and attack on journalism is that there’s a growing community of journalists in exile. It’s becoming a feature of a world we have journalists reporting on their countries based elsewhere because they cannot do that work within the countries.

Ricardo Trotti: Latin America continues to harvest crimes against journalists. “In this first quarter of 2022, 12 journalists have been killed in the Americas, eight in Mexico, one in three in Haiti, one in Guatemala, and the other one in Honduras. The context of widespread violence is organized crime, drug trafficking, and cooperation with the corruption of government officials, police, and paramilitaries, in some countries are the leading causes of this problem.

“In addition to impunity, which raises to 90 percent of the cases, we need to consider that prevention almost does not exist. For instance, most of them or all of the murders occur in the interior of the countries where the government is less present or there is more corruption in those places. Moreover, the protection systems do not work in these countries, and they are very weak and do not have sufficient human and economic resources to operate.

“Since 2018, the law to regulate social media allows to incarcerate users and in 2021 there is another law that allows the state to the government to confiscate the equipment of the users that represent what they call a threat to the revolution.

“Other severe problems for female depressing Latin Americans – the access to public information even though access laws are already in place in most countries this makes it difficult to fight corruption, violence, and poverty, and in addition there is no transparency and governments lie about official data.

“Another widespread problem is the lack of sustainability of the media. For the last couple of decades, now aggravated by the pandemic, the most critical revenue – advertising – migrated to the large platforms. The consequences are yet to be seen in the long term but one of the main one is the news desert that continues to advance, although many native digital media have emerged, for example, it is estimated that 60 of the cities in the interior of Colombia do not have local journalism, the same as in three quarters of Argentina, 14 million people in Brazil and 5 million people in Venezuela live in cities without local journalism,” said Trotti.

In Canada, 340 media have disappeared. More than 2,000 newspapers in the States have closed between 2005-2021, pointed Trotti.

Ruslan Gurzhiy: “The actual Ukraine war started a month ago (in March) between Russia and Ukraine. It’s been up for a while.

“I’ve experienced a lot of threats as a Russian-speaking journalist, here in California, because since 2014 we’ve done several investigate stories about Russian-Ukrainian-American corruption. I went to Ukraine in 2015 and have been covering a lot of Ukrainian corruption since our community here in California, especially in Sacramento, is closely connected to Ukraine.

“Russian-speaking Ukrainian churches are sending humanitarian aid to Ukraine and I’ve done a lot of investigative stories about how this humanitarian aid is being distributed in Ukraine.”

Gurzhiy gave an account of how the police, law and order, the military were corrupted. He also talked about Russian propaganda and disinformation that was spread by outlets from Moscow. He said Russian oil money had a big hand in this effort as well. Gurzhiy gave a very graphic account of what was the reality in Russia and Ukraine and how he was warned and threatened as an international journalist against talking about the facts out of the region.

Jeremy Goldkorn: “It’s really all about propaganda that is very supportive of the state, even for foreign media, it’s a very tough time. The Chinese government has expelled most of the bureaus of The Wall Street Journaland The New York Times, and foreign journalists get harassed all the time on reporting missions, prevented from reporting, prevented from interviewing people, and there is a growing feeling of nationalism that have got worse over the COVID-19 pandemic amongst Chinese people online.

“There’s also a lot of freelance patriotic thuggery of people who harass journalists not because the government told them to, but because they themselves think that foreign journalists are somehow misrepresenting China. It’s hard if you’re a Chinese journalist. In China, you’re either in jail, or you’ve left the profession, or you’re writing essentially press releases.

“The environment in the United States is also very complicated and not very easy. Some of it is because of conflicts within the diaspora community, you have older generation Chinese immigrants and their media that often have roots in Taiwan, that were not necessarily sympathetic to the Communist Party of China, which was Mainland China, then there is the newer immigrants and media companies, many of whom are either directly supported by the Chinese government, are in fact state media themselves, or depend closely on Chinese businesses for advertising or have other professional relationships with Chinese companies which make it very difficult and awkward for them to speak truth to power when it comes to what’s going on in China.

“The there is another bunch of organizations that are organized or funded by one or another flavor of dissidents. There’s one particularly influential organization, ‘Falun Gong’ which is a religious organization that has a big media presence all over the world but is banned in China and is really a sworn enemy of the Chinese Communist Party. So, you have all these different groups vying to speak.

“The problem, as seen from a journalist’s point of view, in a way if you’re working in the United States as a journalist covering China and the Chinese community, if you are seen as anti-China, your media can get boycotted by businesses and people who are associated with the PRC or who want to do business there, and you can get harassed online, and if you have family or personal ties to China, this harassment can be very frightening because you don’t know what’s going to happen back in China.

“If you’re seen as pro-China, you may be the subject of investigation by the United States government which, under the China initiative, sort of grinding to halt now, was a Trump-era government program to investigate scholars and scientists with a background connected to China.

“Many people were wrongfully accused of a malpractice of one kind or another in the milder cases and of spying for the Chinese government in some of the worst cases. Some people who were completely innocent of any of these things have had their careers worked so this is another danger.

“Social media has become an extremely toxic place for journalists and I think covering China, covering Chinese community-related issues, is very bad right now, and this really applies whether you’re seen as pro-China or anti-China,” said Goldkorn.