Fighting for Fair Redistricting Maps in Alabama – Communities of Color React

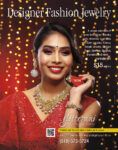

(Above, Inset: l-r): Kathryn Sadasivan, Redistricting Counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund; Felicia Scalzetti, Southern Coalition for Social Justice CROWD Fellow for the Alabama Election Protection Network; Jack Genberg, Senior Staff Attorney of the Voting Rights Practice Group at the Southern Poverty Law Center; and Khadidah Stone, who works with Alabama Forward. (Siliconeer/EMS)

At a briefing hosted by Ethnic Media Services, Nov. 16, the topic of discussion was unpacking the redistricting session and what’s next in the fight for fair maps in Alabama. Speakers include – Kathryn Sadasivan, Redistricting Counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund; Felicia Scalzetti, Southern Coalition for Social Justice CROWD Fellow for the Alabama Election Protection Network; Jack Genberg, Senior Staff Attorney of the Voting Rights Practice Group at the Southern Poverty Law Center; and Khadidah Stone, who works with Alabama Forward – The event was moderated by Anisha Hardy, Executive Director of Alabama Values, a state-based communications hub that seeks to amplify the efforts of grassroots and civic organizations that are on the ground working to build power and break down barrier system participation in communities across the state.

Redistricting is a once in a decade process to draw new district maps to account for the state level population changes in states from the federal level to the local level and ultimately impacts how funding is distributed for core community issues such as health care, schools, and other much-needed services.

On Nov. 3, Alabama legislator passed their new maps despite concerns from grassroots and civic organizations that highlighted the lack of transparency and accountability and accessibility during the process.

Genberg discussed the significance of Alabama’s 2020 redistributing cycle and how some of these maps were passed out of the legislature. Scalzetti discussed the four maps that were passed out of the legislature and discuss how these maps further dilute the voice of minority communities. Stone discussed the lack of transparency and accountability and assess accessibility that we saw during the sessions. Finally, Sadasivan shared what’s next in the fight for fair maps and redistributing litigation, and potential outcomes.

“When communities of color have access to fair and equitable representation they ultimately are able to secure their fair share of resources and improve schools, rebuild roads, and provide better health care, because redistricting happens only once every 10 years. Unlawful redistricting maps harm communities of color for a decade,” said Genberg.

“The Constitution guarantees, everyone in America is represented by political districts that are equal in population number, and are not racial gerrymanders, when race is the predominant factor in drawing a district’s lines and the use of race is not narrowly tailored to comply with the voting rights act or justified by any other compelling governmental interest,” said Genberg.

“A federal court found that 12 of Alabama’s state legislative districts were entered racially gerrymandered in violation of the United States Constitution. Unfortunately, Alabama has once again racially gerrymandered many of its state legislative districts in a complaint filed, Nov. 15, in federal court,” said Genberg.

“Alabama’s redistricting maps intentionally pack and crack black communities in the state denying them the equal protection of the laws in districts where black voters are packed. Black voters are able to elect their preferred candidates but those candidates win by large margins and there are fewer black voters available to vote in other districts.

In other racially gerrymandered districts, black voters are packed and cracked. Their numbers are kept low enough that they are prevented from electing their candidates of choice.

The result of packing and cracking is reduced voting strength of people of color so that voters of color are not able to elect their candidates of choice as often as they would be able to if districts were drawn fairly and legally,” said Genberg.

Alabama’s racially gerrymandered redistricting maps have once again highlighted the importance of new federal legislation like the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act to restore the protections of Section 5 of the voting rights act. This is the first redistricting cycle since 1960 without the protections of Section 5 of the Voting Race Act. Section 5 requires states like Alabama with records of racial discrimination and voting to submit any voting-related changes, which include redistricting plans to the federal government for approval.

Scalzetti said, “With regards to immigrant populations, when these maps are drawn, and they are talking about minority representation, they’re typically talking about black voting age populations. Along with the lack of concern for communities of interest and keeping communities of interest whole, immigrant populations and non-citizens are not taken into account. The effect of these maps on those populations are not adequately looked at or thought about at all.”

“Our main concern with these maps is that they are not reflective of Alabama as a whole. The district lines make it appear that the maps are more reflective and improve communities of interest. A close examination shows the demographics of representation have not changed. There are no additional minority majority or minority opportunity districts in the Congressional state senate and state board of education maps. There is one additional minority majority district in the Alabama state house map,” said Scalzetti.

“However, this still does not represent equity for Alabama. If we look at the actual numbers, in the Congressional map, only one of seven congressional districts is majority black voting age population which represents only 14 percent representation when in reality Alabama has a black voting age population of 25.9 percent. We have a disparity in the actual representation.

Republicans in the congressional map have 85 representation and Democrats have 14 percent representation,” said Scalzetti.

“Our democratic districts and our black majority districts are the same and this is the case in each of the maps, so we have an issue with potentially partisan gerrymandering here as well.

“In addition to that, we’ve seen communities of interest being split in every map. The Indigenous Reservations are split in almost every map and in the house, every single state-recognized Indigenous Reservation has blend split,” said Scalzetti.

“Go to voteprotection.org and click ‘contact your legislator,’” suggested Scalzetti, encouraging people to reach out whether you are part of the immigrant community, whether you are a minority, whether you vote, whether you don’t, whether you are registered, whether you are formally or currently incarcerated, you deserve accurate representation – that’s what redistricting is supposed to be. Send in your concern before January 28, 2022.

The decisions that were made during the redistricting cycle will affect Alabama for the next 10 years and that’s why it was so pertinent for the legislative to draw the lines in the correct manner for the sake of Alabamians.

“When the Census data dropped on Aug. 12, we learned that the population had grown by 5.1 percent and in that population growth it was evident that the population of bipod communities had increased, and the black population specifically is now 25.9 percent; Latinx population increased to 5.3 percent and two or more races triple to 5.1 percent, that’s a total of 36 percent for the bipod communities,” said Stone.

“The legislator would have needed to create two majority minority districts to reach a percentage of representation that would be closely aligned with Alabama’s bipod community population. Since 36 percent of Alabama’s population consists of bipolar communities, having three districts would have been a move in the right direction as well, which would have put the representation in Congress for people of color at 42 percent. At the beginning of the process there were public hearings held across the state so that citizens of Alabama could give their input but we quickly learned that many Alabamians across the state did not like the way that their maps were drawn 10 years ago and they were asking that the legislature worked harder this year in the 2021 to create more equitable maps and maps that made sense for Alabamians and the people that spoke out came from all demographics and all had their own reasons for disliking the maps, but the theme was common – they wanted better representation for their communities. The most common complaint was the split among several districts making it difficult for members of the community to know who represented them,” said Stone.

“From social media messaging to redistricting trainings, to speaking at public hearings, to attending the special session, to emailing texting and making calls to legislators, we have worked day and night to fight for a better Alabama and to ensure that Alabamians have the proper tools and resources to fight with us,” said Stone.

“Any and all elections, between when a voting law is passed, or in this case, redistributing maps, are thereby influenced by the law, despite its compliance with the Voting Rights Act. I think what the rush process in the Alabama legislature this year really highlighted is that, whereby the legislature adopted all of the statewide redistribution maps in a one-week special session. It highlighted the state of Alabama’s failure to comply with the Voting Rights Act and the continued need for the Voting Rights Advancement Act to bring Alabama back under the affirmative protections of the Voting Rights Act,” said Sadasivan.

“During this special redistricting session of the Alabama legislature, Alabama Forward and a number of other groups affirmatively asked members of the legislature whether they had conducted the required analysis under the Voting Rights Act to determine where additional majority minority districts may be required and all of the committee members affirmative that were asked affirmatively stated that they had not conducted a racially polarized voting analysis before packing Congressional district 7, and then cracking the black populations across Congressional districts 1, 2, and 3, and then finally failing to create a second majority minority opportunity district in the Congressional map,” said Sadasivan.

On Nov. 15, various lawsuits were filed challenging HB1, the Congressional map passed by Alabama. Also challenged were SB1 and HB2, which enacted maps from the Alabama state senate district and the Alabama state house district.

“Under the Voting Rights Act and the U.S. Constitution, we’re seeking a remedy that will allow black preferred candidates to win election in two of the seven U.S. Congressional districts in Alabama. Currently, black people are only able to elect candidates of choice in Congressional district 7, which was created in 1992 following litigation under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,” said Sadasivan.