Climate Change Takeaways from COP26: Stubborn Optimism

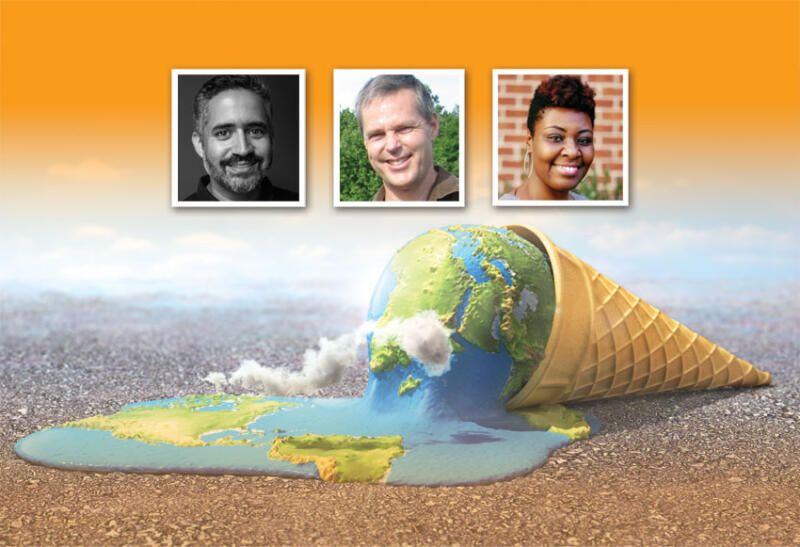

(Above, Inset: l-r): Ramon Cruz Diaz, Sierra Club, President of the Board of Directors, first Latino president of the environmental organization and emphasizes justice and equity on environmental issues; Alex de Sherbinin, Associate Director for Science Applications and a Senior Research Scientist at the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia Climate School and its Earth Institute, an expert in climate migrations; and Dana Johnson, Senior Director of Strategy and Federal Policy at WE ACT for Environmental Justice. (Siliconeer/EMS)

Fresh off the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference just celebrated in Glasgow, environmental leaders and experts examine what was achieved and what was not, including the charge that developed countries blocked reparations to pay for the devastating impact climate change has already had on developing countries. As global migration swells with climate refugees, the lack of resources in these countries will only accelerate the pace of climate change rather than reversing it.

Ethnic Media Services held a briefing, Nov. 19, where speakers – Ramon Cruz Diaz, Sierra Club, President of the Board of Directors; Alex de Sherbinin, Associate Director for Science Applications and a Senior Research Scientist at the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia Climate School and its Earth Institute; and Dana Johnson, Senior Director of Strategy and Federal Policy at WE ACT for Environmental Justice – talked about the climate change threat and COP26 conference outcomes.

“I’m much more positive than negative, about COP26,” said Ramon Cruz Diaz, Sierra Club, President of the Board of Directors. He is the first Latino president of the environmental organization and emphasizes justice and equity on environmental issues. He was speaking from Glasgow, where he had just attended COP26.

“Just the fact that the U.S. had a delegation that were having adult conversations, were a huge difference. Donald Trump, just existing and being a President of the U.S., was a huge harm to a multilateral process and for world collaboration and well-being. It was a big shock, and it will take time for countries to go back, to have trust in the system, to have trust of a dialogue with the United States,” said Cruz Diaz.

“The U.S. made a big difference. It was a very good negotiating team, very committed to the success of the process and the Paris Agreement, that was very positive. In terms of successes, there were the deforestation commitment, the initiative on methane, the developed countries pledging not to do any public financing of coal projects overseas,” said Cruz Diaz.

“I think the signal was very clear, with many commitments, and the UK leading a pledge, to phase out coal. It will take longer of course, at the end. India and China blocked that and wanted to make it as a phase-down instead of a phase-out, the signal is clear that the days of coal are numbered,” said Cruz Diaz.

“We saw the pledges from Bloomberg on taking what was one of the most successful campaign in the history of the environmental movement, the Beyond Coal campaign. They are either closing or scheduling to close more than half of the coal plants, it’s going to be taken internationally and we can then focus on private financing of coal,” said Cruz Diaz.

“I was part of a press conference criticizing the U.S. and EU for blocking the requests from developing countries and most vulnerable countries on the loss and damage part.

“Financial mechanisms that vulnerable countries can get to recover from disasters. It’s more associated with the justice issues. On the domestic front, we have the Justice 40, Build Back Better, that just passed the House of Representatives.

“It’s something we have been dealing with for a number of months and it was very frustrating during the COP when the five moderates from the House held on to the bill. All those things affect credibility of the U.S. in terms of delivering on its domestic agenda.

“The international front is even more difficult. Sometimes you will see articles that would say it’s a disaster because we saw loss and damage not being a big part of it.

“Actually, this was another success of the summit. A proposal came at the last minute from most vulnerable countries. Usually, such proposals take a long time to develop within these conferences, and the fact that again we were having adult conversations about that, is very positive,” said Cruz Diaz.

“The U.S. and the EU, especially the U.S., did not want to commit to a specific financial mechanism for loss and damage because we did not even have the Build Back Better (initiative), we don’t even know if in the midterms, Congress switches, then forgets about any new budget on climate issues. Anything that they would promise now will be subject to then be rolled back by a Republican Congress.

“They didn’t want to commit to something that would actually be very new for the UN FCCC, the Framework Convention on Climate Change, because usually the financial mechanisms that we have had under the Kyoto Protocol are more to support, promote new technologies, and new projects, and leapfrogging technologies into mitigate or adapt to climate change, and not necessarily something that is more of a disaster relief,” said Cruz Diaz.

“You can see how FEMA, within the United States, is quite disastrous. I am from Puerto Rico and the deployment after hurricane Maria was a disaster for the federal agency.

“Imagine what would it take for setting up a new financial mechanism for the whole world to cover for loss and damage. It would probably take a number of years to set it up, to agree on something, then a number of years to design it, then a number of years to populate that funding mechanism. You’re looking into a decade and it will take a long time to do that so developed countries are saying – ‘Well, let’s use better. Let’s start to have the conversation so that we can use the financial mechanisms that we have.’

“Developing countries, in their defense, don’t want that because they know that sometimes that comes with old money in a new mask, and they would like to actually have new money into this. This is the kind of conversation that this process needs to have, and in that regard, I think, it was a big success,” said Cruz Diaz.

“One of the failures is that we are still not where we should be in line to 1.5 degrees, however, we saw an advancement towards that goal,” said Cruz Diaz, who has been following this topic for over a decade.

“You don’t see these as one-off, but you see this as an evolution, and in terms of evolution this was a COP that was a push-forward, rather than a set-back,” concluded Cruz Diaz.

For those who are new to the subject, this is what 1.5 degrees means – according to the Paris Agreement, the U.S. was a big engine and everybody was surprised that it actually had a more ambitious goal of stopping the warming at 1.5 degrees instead of two degrees.

“Eighty-five percent of people have already experienced the consequences of climate change, and for somebody who just lost everything to a natural disaster, 1.5 to two degrees is pointless,” said Cruz Diaz.

“We’ve been obviously striving to get towards the 1.5 degree. We don’t want to get to 1.5 but we want to limit it to 1.5 and yet it’s a bit of an arbitrary threshold. We’ve seen massive impacts already with just under 1°C warming globally.

The RCP 8.5 or 6.0 scenarios – Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) represent different emissions, concentration and radiative forcing projections leading to a large range of global warming levels, from continued warming rising above 4 °C by the year 2100 to limiting warming well below 2 °C as called for in the Paris Agreement – you start hitting temperatures by the end of the century that are up to four degrees warmer than the current and that would just be catastrophic. We want to keep it on the lower end where things stabilize,” said Alex de Sherbinin, Associate Director for Science Applications and a Senior Research Scientist at the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia Climate School and its Earth Institute. He is an expert in climate migrations.

“It does start raising questions of habitability in certain parts of the world as temperatures reach levels that have been unprecedented in the past,” said de Sherbinin.

“We basically have, on the one hand, environmental hazards and their timing, and location, and intensity, and then, on the on the other hand, we have social vulnerability, which is the characteristics of populations. This is something to be aware of, and out of that comes risk, and you may or may not have mobility, depending on a number of other factors, including the government response capacity – do you have a disaster management agency; do you have early warning systems in place; do you have hospitals and other facilities that could take care of people who may be harmed by climate events; also, is mobility itself or migration something that is considered to be a traditional risk management strategy,” said de Sherbinin.

“Migration is generally not perceived of as an adjustment to climate or environmental conditions, so much as a job procurement or income procurement mechanism. Obviously, if your crops are going down, and your income is going down, it may be because you’re facing a drought or extreme flooding a rural and real world.

“Urban migration has increased in many parts of the world because of environmental change but it can put people in harm’s way. A lot of people talk about trapped or involuntary mobile populations, where you essentially lack the means to move because your resources are depleted over multiple droughts, or multiple cycles of extreme events,” said de Sherbinin.

“Most migration will be internal, and if it is trans-boundary, it will likely be in the global South. Most of the refugee-hosting countries are in Africa and parts of Asia, not in Europe and North America.

“Temperature and precipitation are used in various models to help explain migration patterns, but they vary in their effects, which suggests that it’s the economic drivers, the policy, the culture, which still predominate in terms of decision-making when migrants decide where they’re going to move. That doesn’t mean that temperature and precipitation effects are not negligible. In some cases, they can be highly explanatory in terms of understanding how and when people move, and what events are the trigger movements.

“I’ve been doing some work over the years on in planned relocation and resettlement and how much of it’s going to be a small minority of people that might benefit from such programs.

Two reports, one released in September 2021, called Groundswell Part Two, and the first in 2018, have contributed to the evidence base in the area of ecosystem-dependent communities.

Those that depend on rainfall and rain-fed agriculture, and pastoralism particularly, and the point is that there is a real need to improve the lives in climate-proof, for lack of a better term, some of the livelihoods in developing countries, to make them more resilient to the impacts of climate change,” said de Sherbinin.

“If we’re going to address, what amounts to involuntary or forced kind of forms of migration, the modeling framework we used was not to model migration directly, but rather to model future population distributions.

“We find, when you model the regions, most of the developing world, a range of between 48 and 216 million people as potential internal climate migrants within countries by 2050 – Largest numbers are in Africa, which has a very high sensitivity,” said de Sherbinin.

“The UN Migration Network, which focused on the issue of climate migration, has a website that says, the Cancun Agreement and some other agreements have addressed migration head-on and typically they do address it from a global perspective of developing or low-income countries and not the security concerns of the global North,” said de Sherbinin.

Q: India is being asked to scale down its use of Hydro Fluorocarbons, its primary source of coolant. India is a very hot country, is it a fair to ask people to use less HFCs and when the rest of the developed world is driving around in our SUVs, considering how cold the malls are in the United States?

A: It’s a real issue and you know clearly there are a lot of parts of the U.S. where energy is so cheap that people just keep their thermostats cold all day long, even if they’re gone to work. I think it’s clearly something we need to address in the global North. I don’t think it’s necessarily fair though.

The issue around the hydrofluorocarbons – there are substitutes, and I guess developing countries have a longer time frame for transitioning, but that time may be coming up to the point where they need to transition. Subsidies could be made available to low-income countries to make these alternatives more economically feasible, pointed de Sherbinin.

Dana Johnson, Senior Director of Strategy and Federal Policy at WE ACT for Environmental Justice, spoke on the need to focus on environmental justice and combat environmental racism in communities of color.

“In January, President Biden signed executive order 14008, which established the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council and it also established the Justice 40 initiative which states that, say we go back and forth on what an investment or a benefit is, but it’s either benefits or investments from saving money by reducing our carbon footprint and our transitioning away from fossil fuels to what we call, clean energy economy, the money we save in doing that will be reinvested in communities that have a history of being disinvested in, a history of being on the receiving end of, quite frankly, systemic racism in our environmental policies and practices and so the work of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council is to give the administration guidance and recommendation on how to implement Justice 40 in an equitable and just way.

“That body created 128 pages of recommendations that focus on various facets of this particular conversation. How do we move away from fossil fuels; how do we prepare the next workforce; how do we address legacy pollution – it covers the gamut – how do we determine what communities; how do we define disadvantaged communities; what tools do we need to be able to make clear that monies from Justice 40 should go directly to people on this particular block; The idea is that we want to get that granular, and so at COP the United States talked about the ways that agencies and departments were doing that kind of work and it was talked about from an equity perspective, but we felt like the conversation was missing the justice part of it,” said Johnson.

“It was missing the addressing of the legacy of environmental racism that we see in the global South,” pointed Johnson.

“For me, a big source of optimism is the new generation – how clear they see things and how I really hope that when they take command of things, they’re much more aware of what is happening, especially, when it comes from the developed countries, to be much more aware of their responsibilities towards the most vulnerable ones. A viewpoint, but more as collaborators and partners because the knowledge is there already, not only by the scientific community, but by developing countries, by the most vulnerable countries, and they have the right action plans. They need the capacity building, the technologies, and the funding mechanisms to achieve that. That’s what brings me some hope,” concluded Cruz Diaz.