Anti-vax Sentiment, Hardships, Mistrust Fuel Butte County’s Low Vaccination Rates

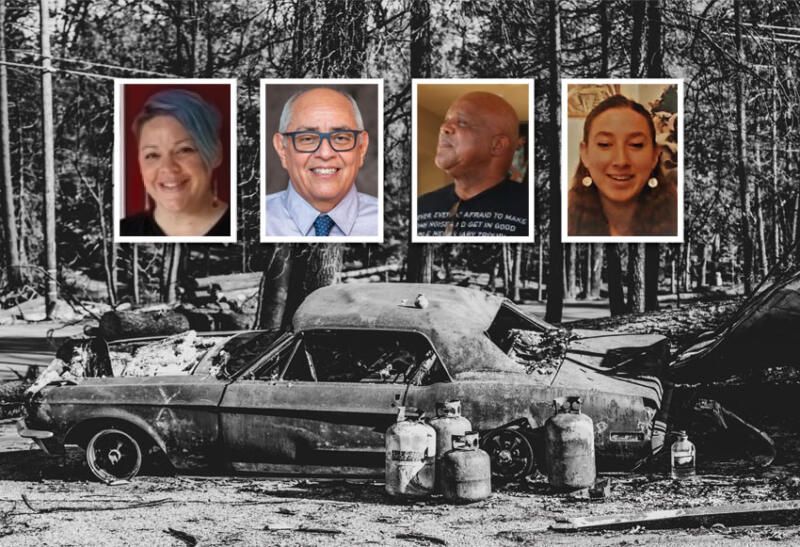

(Above): A view of devastation from the Paradise Fire, in 2019. (Shutterstock). (Inset, l-r): Professor Lindsay Briggs, Chico State University; Angel Calderon, Gridley City Councilmember; Pastor Kevin Thompson, No. 1 Church of God in Christ, Southside Oroville Community Center; and Maya Klein, Inspire School of Arts & Sciences. (Siliconeer/EMS)

At a briefing by Ethnic Media Services, The Center at Sierra Health Foundation and the California Department of Public Health, Dec. 07, speakers – Professor Lindsay Briggs, Chico State University; Angel Calderon, Gridley City Councilmember; Victor Rodriguez, Butte County Public Health Equity Specialist; Pastor Kevin Thompson, No. 1 Church of God in Christ, Southside Oroville Community

Center; and Maya Klein, Inspire School of Arts & Sciences – visit the challenges faced by Butte County and nearby areas in increasing COVID-19 vaccination rates. A special thanks was called to the County Department of Public Health, and to the Publisher of ChicoSol, Leslie Layton for their help with this briefing.

The topic is crucial to the battle to contain the COVID-19 pandemic in California. The challenge of increasing vaccine rates in Butte County, a semi-rural county, 165 miles north of San Francisco, with a population of approximately 226,000 people and one of the lowest vaccine rates in the state, Butte County is in the midst of change, shifting from rural to suburban but still with an agriculture-based economy hit very hard by wildfires, absorbing newcomers from Silicon Valley, as well as wildfire refugees, and with a strong anti-vax sentiment among large sectors of the population.

The county has no mask-wearing mandate. Chico, the county’s largest city, highlights the challenges with soaring housing costs, a growing population of unhoused residents, a deeply conservative political and business leadership.

Victor Rodriguez with Butte’s Department of Public Health presented the latest data on COVID infection mortality and vaccination rates for the county.

“Since the beginning of the pandemic, Butte County has now experienced a total of 22,039 confirmed positive cases with the highest rates occurring between the ages of 18 and 44. Since then there has also been 319 confirmed deaths in Butte County impacting primarily the age group of 65 and older with the highest rates.

“Butte County experienced an uptick in cases in late summer of 2020 due to the return of college-age students to the county to commence classes. A second wave also occurred late in late fall and winter of 2020 due to the increase of family gatherings and celebrations for the holidays. For some perspective, the surge that occurred in late summer were 112 cases reported on Aug. 24, 2020. For the winter wave there were 192 reported cases on Dec. 17, 2020,” said Rodriguez.

“With the authorization of the vaccine in December 2020, there was a decrease in cases by spring, however, with the introduction of the delta variant there was another wave by this past summer of summer 2021, primarily impacting residents who remain unvaccinated and or were fully not fully vaccinated.

“The highest confirmed cases for one day due to the delta variant was 223 cases on Sept. 7, 2021, and for the week of for highest confirmed cases in a week due to the delta variant was 989 cases for the week of Sept. 2 through Sept. 13, 2021. Concurrently, there was also the highest hospitalized cases in that week of 138 cases hospitalized on Sept. 23, 2021, with 26 of those patients in ICU on Sept. 30, 2021,” said Rodriguez.

“Most of the cases were in large populated areas such as Chico and Orville. 50.58% of the total population of Butte County is fully vaccinated. 5.55% is partially vaccinated and 43.87% remain unvaccinated, in which, 39.2 percent of the Native American-Alaskan Native population is fully vaccinated; 57.4 of the Asian American population is fully vaccinated; Black African-American community 40.4 percent; Hispanic and Latino community 44.5 percent; Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islanders are at 63.4 percent fully vaccinated; communities of Multi-race 27.5% and White Caucasian communities 47.1 percent are fully vaccinated currently in Butte County.

“Various ethnic groups provided crucial assistance with quick translation to get documents distributed from the county to the communities and also provided strategic input for these outreach materials and made available in English, Spanish and Hmong.

“Some of the grassroots communities were contacted with outreach efforts such as the Department of Employment and Social Services as part of Project Room Key efforts and to receive information through the capacity of the roles in order for homeless communities and additionally hospital community outreach partners was also crucial for our efforts and particularly with the vaccination clinics and become part of the response.

“Some of the challenges faced through the pandemic were staffing within the department and getting the available bodies in order to get to rural specific communities. Bringing infrastructure and internet and cellular service to those rural communities so they have access to care which unfortunately is negatively impacting their health abilities,” concluded Rodriguez.

Professor Lindsey Briggs, a tenured faculty member with Chico State University’s Department of Public Health and Public Services Administration provided an overview of the changes in Butte County and how they intersect with the battle to contain the pandemic and vaccinate residents.

“In Butte County, we have an unprecedented sort of rise of anti-science attitudes and a rejection of evidence basis. We cling to a lot of our opinions and beliefs rather than facts. Most people are getting their news and their educational knowledge from Social media which is rife with misinformation, becoming more and more politicized and polarized in a lot of different ways.

“We see a lot of echo chambers created on social media and a lot of that has created this information, disinformation, that has been weaponized and lacks sort of a robust educational perspective and a lot of high health illiteracy which makes it really hard for us to present compelling evidence that is helpful to the population, which is what we’re seeing lead to high rates of COVID infection and low rates of vaccination in many of our populations.

“Butte County is also in an unprecedented change in the past couple of years. In 2017, we had the Oroville dam that almost failed; in 2018, the Camp Fire which totally wiped out the town of Paradise; in 2020, we had the North Complex fires which also wiped out the town of Berry Creek; and then this past summer we had the Dixie fire which only touched the top of Butte County but spread northwards. We’ve been living in fire season for really long periods of time which creates a lot of fear and distrust,” said Briggs.

“Butte county is overwhelmingly White. We have a lot of strong pockets of ethnic diversity but overall, Butte County is 86 percent white. If we compare this to native populations, the Navajo Nation has reported that they’re 70 vaccinated because Native American populations tend to be communal and we look out for the public’s health whereas White communities tend to be more ‘me, my family,’” said Briggs.

“Our leadership has really failed us. In this county we have seen a lot of misinformation, some spreading of fearmongering and some other sort of things. We know that in a pandemic, information is constantly changing. The CDC has had to revise some of its statements and compared with lack of science education and understanding of the general populace, this creates more of that distrust.

“If you go out in view county almost nobody’s wearing masks which is really difficult because we don’t have a mask mandate. When we look at the chaos that’s happened at some of our school board information has been really bad because people want their kids back in school but don’t want them to be vaccinated, don’t want them to be wearing masks, and that’s just a recipe for disaster. We need strong leadership,” said Briggs.

Angel Calderon, a long-time community outreach worker in public health and was recently elected to the Gridley City Council, talked about vulnerability with residents.

“The agricultural farm worker suffers tremendously on the pandemic and continues to do so. In 2020, between May and June, Gridley had the highest infections rates in the county and basically very little effort to educate the population. The stigma associated with the COVID prevented many of agricultural workers from seeking testing, assistance from the established health agencies.

“The Myron seasonal farm workers had a really difficult lifestyle. People don’t know exactly what the lifestyle is how they pay the bills, how they pay the rent, how they make ends meet, it’s very difficult for them to access a lot of our services. The fact that approximately 70 percent of our agricultural farm workers are undocumented and a lot of times, the stigma associated with procuring health services is definitely a factor that prevents them from procuring these services.

“Farm workers, if they don’t work, they don’t eat, very simple. They’re not like everybody else. We have to pay attention that we have to pay them because they’re essential workers. We need literature, we need education, we need a strong presence from Public Health in the city, and in surrounding areas,” said Calderon.

Pastor Kevin Thompson with the Number One Church of God in Christ and the Southside Oroville Community Center gave his thoughts on the struggle to raise vaccine rates.

“We take our four custom built trailers that’s outfitted with showers, stackable washers and dryers, toilet, pedestal sinks, all on the 32-foot trailers, to the communities in Chico, Oroville, Berry Creek, throughout Butte County and serve individuals that are affected because of the the Camp Fire, in Paradise, the Bear Fire, the North Complex Fire. We have had an opportunity to speak to many of the people that are displaced and some of them are fearful about this vaccine; some of them can care less one way or another,” said Pastor Thompson.

“We all know that unvaccinated have the potential of becoming super spreaders. We understand where we live we’re in the 40 percentile of individuals that are vaccinated. That’s way too low, and surrounding errors such as Bigs, Magalia, and Paradise, those areas, the percentage is even lower, so we want to really push our community and our leaders to really do something to engage individuals to get vaccinated,” said Pastor Thompson.

“The vaccination disparities are just a big difference in our community versus other communities. It’s a semi-rural community such as ours here in Butte County that has been left behind. We are very poor community and the social economic disparities in this area are great. Many people migrated in Oroville due to the burns. Getting vaccinated is not the most important thing on their mind. They’re more concerned about rebuilding their homes, make a way for their families with the food insecurities. Lack of knowledge and understanding about the virus and rumors have become stumbling blocks in our community and the most important is simply misinformation,” said Pastor Thompson.

Maya Klein, a high school student in Chico gave her perspective on COVID as a high school student.

“My high school, Inspire School of Arts & Sciences, is a bubble within Chico. Our student vaccination rate is 82 percent, and our population generally follows mask and hygiene guidelines. Our 2020-2021 school year remained almost entirely on Zoom classes, following a one-by-eight schedule in which we delved into a single class for each month until the end of the school year.

“During this time other high schools within Chico had returned to in-person learning and as a result student COVID cases began to increase. This was, and still remains a reality, that I feel relatively detached from. Inspire students have witnessed from afar, a local unwillingness to adhere to safety guidelines which is obvious when entering the community, whether that be in a grocery store or in another school. At the height of the pandemic, our COVID hospitalization rates were terrifying which was a matter reflected in the extremely painful experiences of people. However, it was not reflected in the actions of the community, a culture and climate of denial grew out of that year and continued into this year.

High school has now returned entirely to in-person learning along with all other local high schools and with that return came an extremely apparent silence when it came to addressing the effects that the pandemic has had on our community. Both in and out of school, the conversation about covet has ceased,” said Klein.

“My age group now faces a reality in school where hygiene and safety is recognized but the phenomenon of the pandemic itself now goes unnamed. Young people were thrown into the pandemic at a formative age of mental health facing all the nuances of becoming a young adult and this was coupled with a global health crisis that disproportionately hurt our community. Though these factors affected every one of my peers and myself, the climate in Butte County has made it difficult to start this conversation of healing or even of initial acknowledgement. COVID has become something of a taboo topic where misinformation has fed fear and has led to an overall sense of confusion and denial even within my own peer circles where our families have been personally affected by the horrors of COVID,” said Klein.

“There is a sense of trepidation and hesitation to approach the subject. I believe that there are multitude of reasons that this is the case first and foremost being that a conflict zone exists which are community fears in sighting with such opposition over the topic of COVID. It’s difficult to have a conversation in with anyone in Butte County without polarizing the topic. Exploring how to walk the line of this polarity has been an issue not yet resolved.

“In Chico, especially in an educational environment, it’s vital that students feel an acknowledgement of this massive event that the globe is still experiencing however because there is no written rulebook for how to approach the conversation, it has not been brought up. As a result, we have not begun to face the reality in our community, which is one of low vaccination rates, lack of information, and continued disease as a young person living in a fortunate bubble of good health,” said Klein.

“Protests from our own medical workers at our hospital on anti-masking and vaccinations, Butte County seems to be defined by disastrous wildfires which emphasize the disparity and calamity of COVID. Youth are at the center of this, frequently being faced with emotional hardship and well-being at the same time. However, these adversities are unacknowledged which only extends the hardships.

“COVID-19 is an unfathomable reality that the world is still enduring. Starting a conversation with our youth is the first step in beginning to grapple with how it affects us as a whole. Butte County has yet to realize this, but I hope that they can turn to their young population to begin that dialogue of healing,” concluded Klein.