An Old, Deft Hand to Captain Indo-U.S. Relationship – A Formidable Tenure awaits Taranjit Singh Sandhu

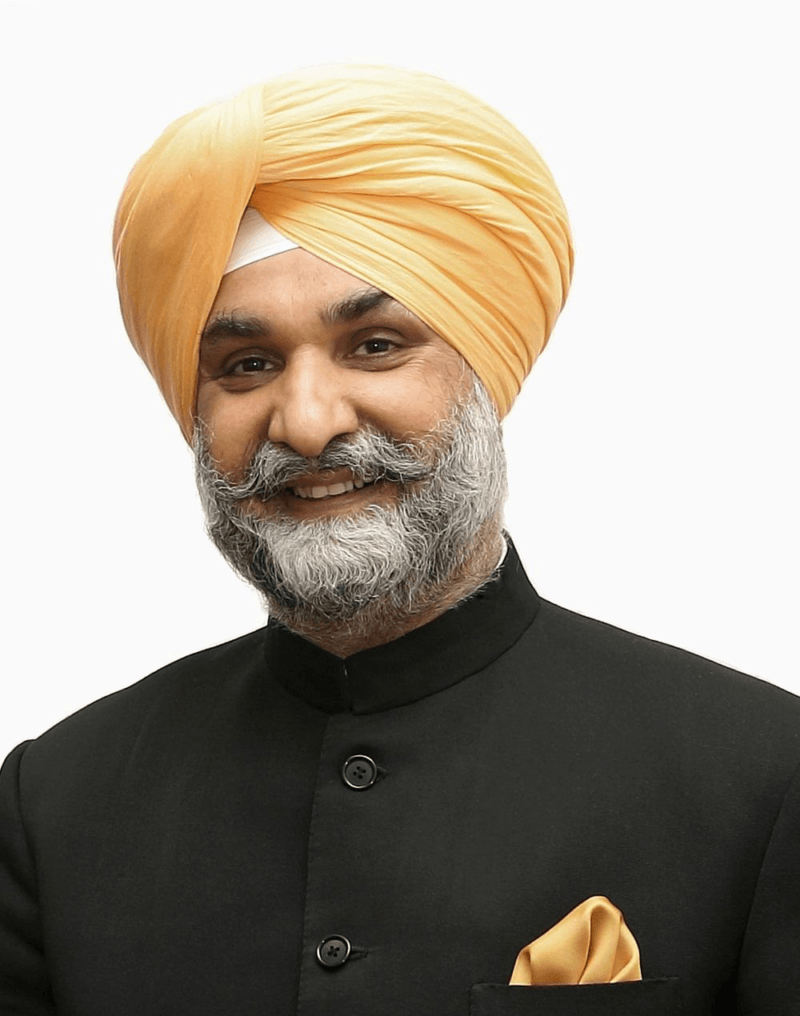

(Above): Indian Ambassador to the United States Taranjit Singh Sandhu. (MEA/Gov’t of India)

Taranjit Singh Sandhu has been appointed as India’s ambassador to the United States of America, replacing Harsh Vardhan Shringla who has taken charge as the country’s 33rd Foreign Secretary.

A 1988-batch Indian Foreign Service officer, Sandhu has been thrice posted in the U.S., first as the First Secretary (Political) at the Embassy of India in Washington (1997-2000), then in India’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York (2005-2007), and again as Deputy Chief of Mission at the Indian embassy in Washington (2013-2017) that provide him a wide range of experience to draw upon.

Regarded as a leading U.S. expert in Indian diplomatic corps, his appointment, welcomed whole heartedly by Indian-Americans, the U.S. business and think-tank communities, comes at a time when the India-visit of U.S. President Donald Trump is slated for next month and New Delhi is facing the heat for its legislative sanction to the Citizenship Amendment Act and abrogation of Article 370 in erstwhile Jammu & Kashmir.

U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, a champion of free trade sans unfair competition and popularly known as the “battle-scarred veteran of trade negotiations”, arrives ahead of Trump to prep up the $10 billion trade agreement that had been pending even before Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s October 2019 U.S. visit for Trump’s imprimatur.

The superpower may be perceiving India as the fulcrum of its Asia policy, but of late, it has been mounting pressure on India to remove price caps on U.S.-imported medical devices such as heart stents, knee implants and other medical devices, relax e-commerce rules, even as American firms, Amazon and Walmart, have established a virtual duopoly on India’s e-commerce, and roll back tariffs on farm goods – strawberries apples, walnuts, almonds, and Harley-Davidson bikes.

It also vies to enter the lucrative Indian markets for dairy or poultry.

The Indians have yielded some ground by removing caps on medical devices and tariffs on a few U.S. goods, but not without obtaining a reciprocal partial restoration of concessions for about 2,000 Indian imports under the U.S.’ Generalized System of Preferences (GSP).

Still the U.S. is pushing for $5-6 billion in additional trade for U.S. goods in return for reinstatement of India for GSP privileges and to widen the scope of the deal.

Though other deals, revolving around defense and energy purchases from the U.S. are also on the anvil, the trade pact remains of paramount significance to both nations.

It will allow Trump to register a second policy victory in succession to the “phase one” trade deal it closed with China, and both these would earn for him the much-needed credit for his Presidential re-election.

To India that in November-end pulled out of the China backed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the biggest regional trade partnership that the world could have seen, due to reasons of both an adverse trade balance and protectionism, it’s a chance to expand the trade outreach with the U.S., especially in areas of pharmaceuticals, chemical and engineering, while also plugging its goods and services trade deficit with the U.S. that stood at $25.2 billion in 2018 (USTR Report).

At a time when the Modi government faces the twin challenges of highest unemployment rate in last four and a half decades and an economy clocking the lowest growth rate in five years, further exacerbated with a high oil import bill, tapping the potential of diversionary investment flows sound an immense prospect.

U.S. manufacturers seeking different origination destinations to move away from their excessive reliance on Chinese production can be lured to India if the latter also moves fast on its reforms and innovations in its infrastructure, land and labor policies.

A recent UN trade and investment report talked of trade diversionary benefits of $755 million in additional exports from India in the first half of 2019, and forecasts gains of close to $11 billion to India in future.

Another vulnerability of the Indo-U.S. relations that the new envoy to heed is the emerging Iran factor and India’s position in the context of the Middle East crisis which may be assumed to have been averted for now but imbues fragility in long term regional peace and stability.

The U.S., having worked out its energy independence, is keen to supplant Iran as a significant supplier of crude and petroleum products to India hat is the third largest consumer of energy and hence its vital interests may not as much lie in ensuring peace in the region.

In fact, this loss of U.S. interest has only resulted in Iran cozying up to China.

With India’s investments in spheres of culture and economy that includes the Chabahar port, allowing it access to Eurasia, and affinity for cheaper Iranian crude, supply of which was partially restored due to waivers granted to New Delhi in the U.S.’ recent “Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act,” New Delhi will have to sustain a fine balance.

Therefore, maintenance of exceptionally good relations with Iran and actualizing the potential of India as a counterweight to an aggressively expansionist China, along with resolution of matters that may crop up will need to be on India’s to-do list.

As the U.S. Presidential election inches closer the Trump Administration that has always sought to limit migration to the U.S. across the board and has blown hot and cold over this issue, will further clamp down on the use of H1-B visa programs.

Indian nationals make up 70% of the work permits issued for high tech work by the U.S. and have been greatly impacted by Trump’s “Buy American & Hire American” policy.

Clearing up of obstructions to the flow of talent via H1-B non-immigrant visas from India to the U.S. is something that New Delhi has viewed as a significant element of the strategic bridge between the two countries will also form a vital challenge to Sandhu.

Based on common values, the rule of law and democratic principles, and shared interests in promoting global security, stability, and economic prosperity through trade, investment, and connectivity, the two countries have sought a bilateral partnership and the seasoned diplomat’s diplomatic work has been well chartered out to build and improve commercial relations, and continue collaboration in advancing strategic partnership by maneuvering Trump’s repertoire of assertion, aggression and arbitrariness, matched with his skillful diplomacy, tough negotiation and strategic vision to fulfill India’s interests.

Sandhu is expected to make a terrific team with External Affairs Minister, S. Jaishankar, who himself has come up from within the ranks of the revered foreign services, was his boss in Washington in an earlier stint and is widely acknowledged as one with deep familiarity with the powers that New Delhi needs to balance – the U.S., Russia, China and Japan, much on the lines of what was accomplished by his predecessor Shringla, who displayed dynamism and responsiveness.

A few trivia on Sandhu; he shares the same alma mater, St. Stephen’s College, with Shringla, and his wife, Reenat Sandhu, is also an Indian career diplomat and officiates as India’s ambassador to Italy and San Marino.