|

|

|

ADVERTISEMENTS

|

|

PREMIUM

- HAPPY HOLIDAYS!

- Siliconeer Mobile App - Download Now

- Siliconeer - Multimedia Magazine - email-Subscription

- Avex Funding: Home Loans

- Comcast Xfinity Triple Play Voice - Internet - TV

- AKSHAY PATRA - Bay Area Event - Sat. Dec 6

- Calcoast Mortgage - Home Loans

- New Homes in Silicon Valley: City Ventures - Loden Place - Morgan Hill

- Bombay to Goa Restaurant, Sunnyvale

- Buying, Sellling Real Estate in Fremont, SF Bay Area, CA - Happy Living 4U - Realtor Ashok K. Gupta & Vijay Shah

- Sunnyvale Hindu Temple: December Events

- ARYA Global Cuisine, Cupertino - New Year's Eve Party - Belly Dancing and more

- Bhindi Jewellers - ROLEX

- Dadi Pariwar USA Foundation - Chappan Bhog - Sunnyvale Temple - Nov 16, 2014 - 1 PM

- India Chaat Cuisine, Sunnyvale

- Matrix Insurance Agency: Obamacare - New Healthcare Insurance Policies, Visitors Insurance and more

- New India Bazar: Groceries: Special Sale

- The Chugh Firm - Attorneys and CPAs

- California Temple Schedules

- Christ Church of India - Mela - Bharath to the Bay

- Taste of India - Fremont

- MILAN Indian Cuisine & Milan Sweet Center, Milpitas

- Shiva's Restaurant, Mountain View

- Indian Holiday Options: Vacation in India

- Sakoon Restaurant, Mountain View

- Bombay Garden Restaurants, SF Bay Area

- Law Offices of Mahesh Bajoria - Labor Law

- Sri Venkatesh Bhavan - Pleasanton - South Indian Food

- Alam Accountancy Corporation - Business & Tax Services

- Chaat Paradise, Mountain View & Fremont

- Chaat House, Fremont & Sunnyvale

- Balaji Temple - December Events

- God's Love

- Kids Castle, Newark Fremont: NEW COUPONS

- Pani Puri Company, Santa Clara

- Pandit Parashar (Astrologer)

- Acharya Krishna Kumar Pandey

- Astrologer Mahendra Swamy

- Raj Palace, San Jose: Six Dollars - 10 Samosas

CLASSIFIEDS

MULTIMEDIA VIDEO

|

|

|

|

|

LITERATURE:

Maverick Malayali: Vaikom Muhammad Basheer

Literary critics and the common man alike were won by the pathbreaking, disarmingly down-to-earth literary style of Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, the Malayali novelist-short story writer, humanist and freedom fighter who is fondly remembered as the ‘Beypore Sultan’. Siliconeer offers a tribute on the Kerala writer’s birth centenary.

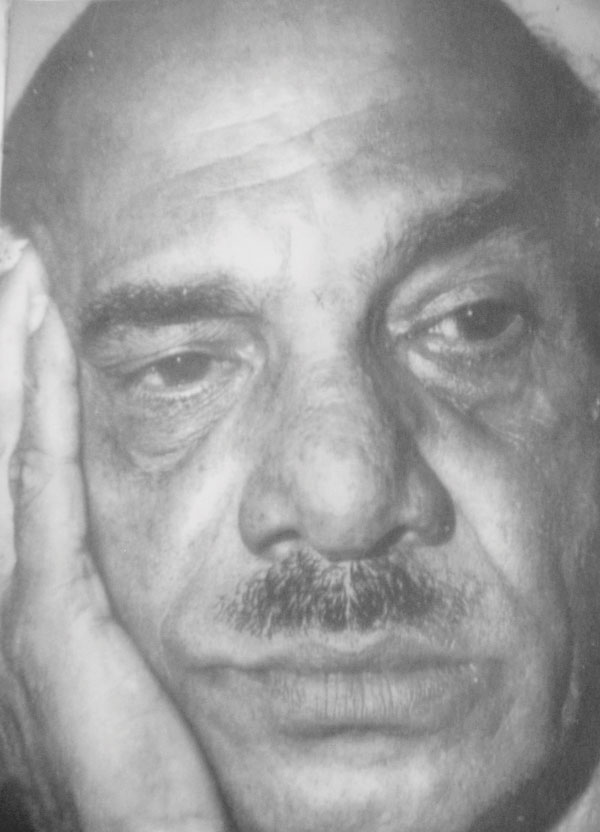

(Above): Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, a titan of Malayalam literature.

Literary critics and the common man alike have been making a beeline to the home of Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, fondly remembered as the “Beypore Sultan” for taking Malayalam writing off the beaten track.

“Basheer belonged to that rare genre of artists who love the world with all its imperfections rather than to those who go on trying to change it since they can love only a perfect world,” poet and critic K. Satchidanandan writes in a tribute in Frontline magazine. “It was this understanding of evil as an organic part of creation and the identification with the outcastes, even those the world considers clowns, idiots, cheats and villains whom his magic wand converted into lovable human beings that helped Basheer redraw the map of Malayalam fiction many decades ago.”

The house in Vylalil Veedu in Kozhikode district and the tree under the shade of which Basheer relaxed in an armchair have become part of legend as Kerala celebrates the birth centenary of the novelist-short story writer, humanist and freedom fighter.

Basheer spent many years there with his wife Fabi, son Anees and daughter Shahina after release from jail for taking part in Gandhiji’s Salt Satyagraha in 1931.

Born on January 31, 1908, Basheer was a maverick to the hilt. He paid scant regard to grammar and syntax preferring rustic language and kept the British Raj fuming with his anti-establishment journal Ujjeevanam (Rejuvenation).

“Basheer used to say he was never sure about the Malayalam alphabet. This apparent inadequacy compelled him to invent an idiom closest to the everyday life of Malayalis which revolutionized the art of story-telling,” Satchidanandan writes.

Conferred the Padma Shri in 1982 two years before he died, he is believed to have once used a copper citation he received for his role in the Independence movement “to chase away a fox that sneaked into his house compound.”

During those days, he was on the brink of starvation and worked as a newspaper seller, fortune teller, loom fitter, cook, hotel manager, accountant, fruit seller, sports goods agent, watchman, and cowherd.

Basheer also spent five years among Hindu ascetics and Sufi mystics.

His Mathilukal (Walls), a memoir on his jail terms was turned into celluloid by noted filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan with Mammootty in the lead.

After watching the film, Basheer told Adoor in a lighter vein that he looked “more handsome” than the matinee idol in his younger days.

His penchant for humor was seen in his writings, which combined it with pathos, love for fellow-beings and faith in the basic goodness of man.

Basheer took the plunge into active politics while in the fifth grade. When Gandhi came to Vaikom for a demonstration to demand entry for lower caste people into temples, he managed to meet him and touch his hand, a memory he often relates in his writings.

His works mostly revolved around the Muslim community in North Malabar but had a universal appeal in that they were translated into 19 Indian languages, and English by Ronald Asher.

He wrote 13 novels and 13 collections of short stories besides several articles, essays and plays. His first novel Premalekhanam (Love Letter), a humorous tale of the affair between a Nair youth and a Christian woman published while in jail, and Balyakalasakhi (Childhood Friend) in 1944.

Much in the nature of some great Western literary figures like Friedrich Nietzche and Nikolai Gogol, Basheer, too, suffered mental breakdowns. A famous work, Pathummayude Aadu (Pathumma’s Goat), was written while he was under treatment at a mental asylum in Thrissur.

His decision to invent an idiom that is closest to the everyday life of Malayalis revolutionized Malayalam fiction. He could make his fictional world possible only by radically altering the status quo-ist vocabulary, according to Satchidanandan. Ordinary words picked up from the streets and the inner courtyards of Malabar homes gained a new vibrancy and artistic aura when Basheer employed them in his fresh narrative contexts. His seemingly artless manner had behind it an unarticulated yet profound theory about the use of language in contemporary fiction that taught different lessons to future writers. His decision to invent an idiom that is closest to the everyday life of Malayalis revolutionized Malayalam fiction. He could make his fictional world possible only by radically altering the status quo-ist vocabulary, according to Satchidanandan. Ordinary words picked up from the streets and the inner courtyards of Malabar homes gained a new vibrancy and artistic aura when Basheer employed them in his fresh narrative contexts. His seemingly artless manner had behind it an unarticulated yet profound theory about the use of language in contemporary fiction that taught different lessons to future writers.

He has been a seminal influence in Malayalam literature.

“While the detached humor in O.V. Vijayan, V.K.N [V.K. Narayanankutty Nair], M.P. Narayana Pillai and Paul Zacharia belongs to Basheer’s lineage, the stylistic simplicity and lyrical quality of Madhavikkutty (Kamala Das), M.T. Vasudevan Nair and M. Mukundan — writers very different from Basheer — can be traced to the same unique narrative heritage,” writes Satchidanandan.

Trained in Arabic at home by a musaliyar, Basheer learnt his Quran by the age of eight. Then he studied Malayalam and English, and read his first storybooks from a friend named Potti, which might have stirred in him the desire to tell stories. The names of Mahatma Gandhi and other leaders of the freedom struggle excited the young boy.

The call of freedom took Basheer to Malabar, the centre of the nationalist activities in Kerala. He joined the Al-Amin newspaper run by the patriot, Muhammad Abdu Rahman. Basheer participated in the Salt Satyagraha on the Kozhikode beach that landed him in jail. Now he began to feel that Gandhi’s peaceful ways would not earn freedom for India; he was fascinated by Bhagat Singh and his comrades and moved over to Ujjeevanam (Rejuvenation), which had now turned from a Congress journal into the mouthpiece of the armed struggle against the colonizers. Basheer had to go underground to evade arrest. That was the beginning of seven years of wanderings in a variety of disguises: as a Hindu mendicant, a palmist, a magician’s assistant, an astrologer, a private tutor, a tea shop owner.

He also went to meet the filmmaker V. Shantaram in an outlandish outfit hoping to join the film industry. Shantaram asked him to learn Marathi and come back. Before he could learn Marathi, a certain Gajanan, impressed by his language skills, employed him as a tutor. He was asked to teach mathematics, and Basheer had no choice but to leave the job and move to Mumbai where he became a physician’s assistant in Kamatipura, the haunt of sex workers, transgender persons and thieves. Next he ran a night school in Bhindi Bazaar, teaching basic English. It was then that the sea called him and he found himself sailing as a khalasi on SS Rizvani carrying Haj pilgrims to Jeddah via the Red Sea. On the way back he landed in what are now parts of Pakistan. He served in a hotel in Karachi and then as a proofreader’s copyholder in the Civil and Military Gazette.

Satchidanandan offers a thoughtful, affectionate critique of Basheer’s writing and style in his long tribute in Frontline.

“Basheer’s language is not literary if literary means deliberately sophisticated and packed with Sanskrit words; it is not philosophical if philosophical means filled with strained thoughts and ideas and references, as exemplified by some writers celebrated as philosophical. But it is precisely by being non-literary — easy, natural and deceptively simple — that Basheer distinguishes himself from ordinary writers who strain after effects even while saying the most trivial things. It is by appearing non-philosophical that Basheer achieves a visionary quality that is inaccessible to those who pack their fiction with borrowed or inane ideas. Basheer’s optimism comes from a robust acceptance of tragedy, and not from the avoidance of confrontation with the embarrassing contradictions of existence.

“Basheer’s humor, too, springs from his grasp of the paradoxes of existence. He combines a cartoonist’s eye with a philosopher’s vision in portraying his characters as in Ntuppuppaakkoranendarnnu (My Granddad had an Elephant), Sthalathe Pradhana Divyan (The Most Important Holy Man of My Place), Mucheettukalikkarante Makal (The Card-Sharper’s Daughter), Aanavariyum Ponkurisum (Aanavari and Ponkurisu – nicknames for Raman Nair and Thoma), Viswavikhyatamaya Mookku (The World-renowned Nose) and other stories. He was one with the ‘progressive’ writers in empathizing with the hapless and in upholding hope in man and the possibility of change, but he went beyond them while looking at the human condition in its many hues and dimensions, including the spiritual that remains an unstated undercurrent in his narratives of life.”

Basheer belonged to a generation fed on rigid ideologies and arid experiences, Satchidanandan writes, but he picked up his tales from the throbbing warmth of life’s poetry. During about half a century of his creative career, he published only 30 books from Balyakalasakhi (1944) to Sinkidimungan (1991) but every one of these 2,200 pages is world-class literature. He created his own language within language (having abandoned English in which he had attempted his first novel), polished, edited and re-edited each line he wrote until it shone like crystal: clear, sparkling, many-faced.

“Outwardly, most of his stories deal with the lives of Kerala Muslims, but it will be a grave mistake, as some foreign scholars such as Ronald Asher, his first English translator, has done, to reduce Basheer’s fiction to its ethnic content. At the deeper level, they are tales of men and women everywhere, trapped in the ironic irrationality of the human condition,” writes Satchidandan.

|

|

|

|

|

|