Virus reopens old wounds for Sioux of Dakota

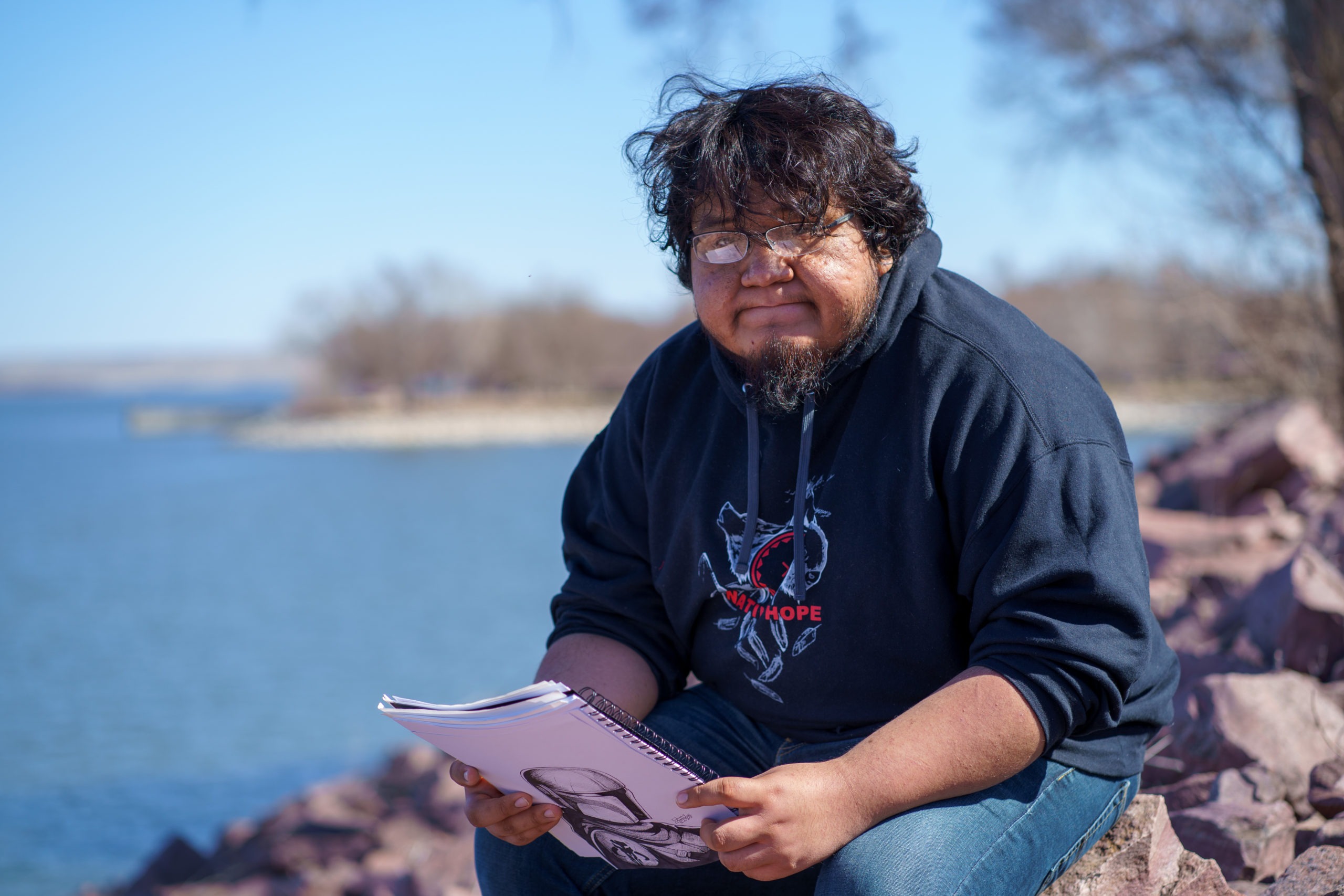

Dennis Metcalf, a Sioux tribe member, fears that the pandemic could wreck his vulnerable community (kerem yucel)

Lower Brule (United States) (AFP) – Like many Native Americans living on reservations in the United States, Dennis Metcalf has faced poverty, hardship and sadness, and now he fears the coronavirus outbreak could devastate his community.

Metcalf, a 23-year-old Sioux from the Crow Creek tribe in South Dakota, started drawing when he was a boy to escape boredom, and now it is an outlet for his darker emotions.

“I grew up in a very poor family,” he told AFP near the small Wild West-style town of Chamberlain. “I didn’t have any toys and sometimes we didn’t even have power, so we didn’t have TV or electronics.”

Among his heavy metal-inspired sketches is a portrait of a calm young woman with braided hair — his late sister Nicole, a casualty of the high suicide rate on the reservations.

The threat of coronavirus has further darkened the outlook for vulnerable Native American populations.

“I’m very afraid that if the virus will spread in the reservation, it will start affecting my family members. I am worried sick for them,” Metcalf said.

Tribal officials have responded to the global health crisis by placing signs along roads ordering travellers not to stop as they drive through the Crow Creek reserve.

Their Sioux neighbors in Lower Brule have imposed a curfew on their approximately 1,000 members and are now considering quarantining their entire territory as others have already done.

– Grim echo of colonial smallpox –

“The tribes have been a lot more proactive than the state,” said Boyd Gourneau, Lower Brule Sioux tribe chairman, expressing frustration that South Dakota has issued no general containment order.

Sitting in front of a buffalo skull in the tribal council room built in the shape of a teepee, he said the pandemic has echoes of the infectious diseases brought by Europeans which decimated Native American people.

British colonialists in the 18th century are accused of wiping out tribes by deliberately giving them smallpox via infected blankets.

“It’s an instinct — I didn’t live through the smallpox blankets, but we heard enough stories that it’s reactive,” said Gourneau.

– No jobs, poor healthcare –

The damage that the current virus could cause to some of the most disadvantaged communities in the United States is made clear every day to Trisha Burke and her colleagues at Native Hope, a non-profit group.

Astronomical unemployment, food shortages, alcoholism, poor health and a reliance on state subsidies and food stamps — Burke said “there are a lot of factors” at play in conditions she describes as “a different world, Third-World-ish.”

How can you wash your hands in homes without running water or electricity, and what do you do if you get infected as healthcare is so limited, she asks.

“Most of these reservations do not have hospitals per se, they have clinics that are overrun already and underfunded,” she said.

“COVID presents an extra layer of difficulty. They may have to travel three hours to get to a place where they could be treated.”

Social distancing guidelines might seem easy out on the Great Plains of North America, but the tattered doors of houses and caravans hide the reality of life in this picture-postcard landscape.

“The housing shortage is bad. You have maybe seven or eight families living together, sometimes 20 to 30 people in one house,” Melissa Johnson, program unit director at the Lower Brule Boys and Girls Club, who grew up with 12 brothers and sisters, told AFP.

“You can imagine, everybody piling on top of each other. That’s probably why everybody is so scared.”

– Finding solace –

Her mother Toni Goodlow, 63, a probation case manager, is a linchpin of the tribe, organizing Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, helping young parents and offering a sympathetic ear to everyone’s anxieties.

But she says she is sometimes “tired of being the strong person.”

“I have my own fears too,” she admitted behind her gap-toothed smile and sunglasses that reflect the peaceful waters of Lake Oahe.

She finds solace each morning by burning sage, cedar and sweet grass in a “smudging” ritual.

“Everybody has different ideas of what it means to us. We don’t talk about it. We do it and that’s it.

“That’s just a spiritual thing but we also believe that it’s killing the virus.”

Disclaimer: Validity of the above story is for 7 Days from original date of publishing. Source: AFP.