The Sino-Indian Wuhan Symphony: A Step at a Time

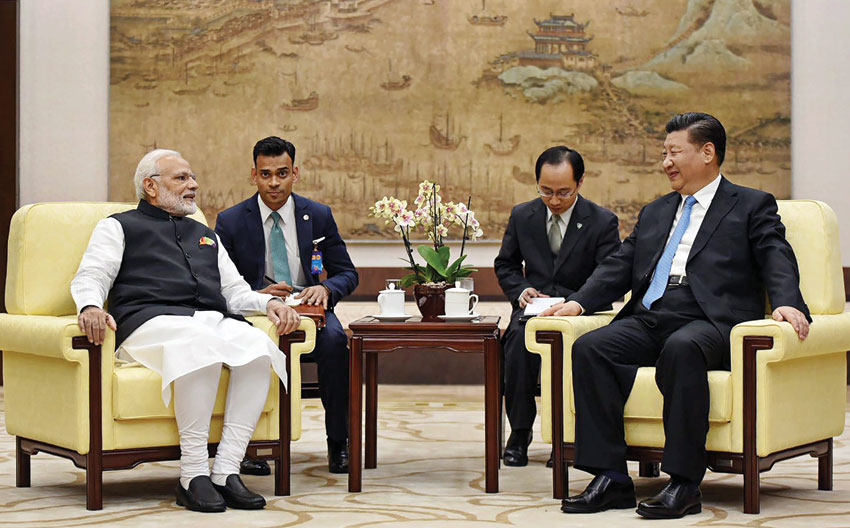

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with Chinese President Xi Jinping visit an exhibition at Hubei Provincial Museum, in Wuhan, China, April 27. (PTI/PIB)

The two-day Sino-Indian informal summit between India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and China’s President, Xi Jinping, that took place, April 27-28, marked a new chapter in the relationship between the two global players which collectively comprise more than 40 percent of the world population. The venue of the meeting was Wuhan in Central China, home to the famous villa of Mao Zedong or Chairman Mao, the founding father of People’s Republic of China, and the place where Mao hosted U.S. President Richard Nixon for the historic meeting of February of 1972, during the height of the Cold War, writes Priyanka Bhardwaj.

In an increasingly new environment of international relations Beijing according the place of equal partnership to New Delhi may be seen as a signal of changing times, notwithstanding tensions emanating from mutual mistrust, long standing issues, and military standoffs, particularly the 72-day Doklam impasse of last year, that had plummeted relations to an all-time low and both countries deciding not to dwell on the specifics.

Despite no set agenda for the talks or any protocol for elaborate diplomatic events, or for that matter any agreements concluded, or customary joint statement issued, the meeting represented a shift from the past and unprecedented at many levels, raising hopes for a peaceful and prosperous future for Asia, if not the world.

The atmospherics were apparent right from the start as the Chinese President hosted Modi on a one-to-one meeting, even though the Indian Premier is slated to visit the country again for the summit of Shanghai Cooperation Organization, another platform of coherence, in Qingdao.

The strategic rapprochement of the two leaders was most possibly premised on the realization that an aggressive stand would be futile in the quest for development and peace between the two countries, sans which, “the Century of Asia,” as once predicted by Mao, should remain an unfulfilled prophecy.

However, given the impressive profiles of both powerful leaders – while Xi enjoys the second place in the international pecking order, in the domestic scene he has been raised to the status of Mao Zedong last October, Modi dominates India’s polity with his unmatched charisma and mandate – it can be reasonably expected that an understanding between these two powerful personalities has a potential to translate into something bigger.

The “rebalancing” talks hit at many converging notes, achieving – an understanding to float a joint Indo-China initiative for economic project in Afghanistan, both leaders agreeing to impart “strategic guidance to their respective militaries to bridge the trust deficit, recognition of “common threat” of terrorism and partnering to counter terrorism, strengthening of dialogue mechanisms to address issues of dispute and sensitivity, Chinese agreeing to balance trade, for the first time, and enhancement of policy coordination in the form of China India plus one or China India plus X neighboring countries.

Both countries did not dodge away from touching upon the boundary dispute, but only to endorse the work in progress of special representatives.

The success of this meeting also lies in the understanding that both the leaders have agreed to hold more of such informal summits in future that could allow them to exercise joint influence on economic development in the region and perhaps an incremental settlement of their long-term disputes.

However, the success of this summit and future ones is dependent on India having done its homework in reconsider and drawing a plan to address diverse contentious but legitimate issues it has with China.

There is the question of China’s economy being five times larger than India’s and the Indo-Chinese trade that is currently heavily skewed in China’s favor.

Figures reveal that Indian imports to China are $72 billion, while its exports to China are $12.5 billion and any balancing would not happen overnight.

Apart from the un-demarcated borders and contestations there is also New Delhi’s inability to cave into Beijing’s wish to end its protest of CPEC that is designed to run through the Pakistan occupied Gilgit-Baltistan region of Kashmir.

Another crucial concern is keeping harmony with allies such as the U.S. and other European countries who recently reiterated that, “New Delhi is a ‘balancing power’ in the region (Asia).”

But as in geopolitics there are no permanent friends or permanent enemies and President Donald Trump’s declaration of “America First” doctrine, India will need to rethink on keeping allies without allowing any compromise on its own interests.

India is already facing U.S. opposition at WTO for giving export subsidies that the U.S. feels is detrimental to its workers and the Trump regime is already pulling up India by cracking down on Indian H-1B visa holders.

While it may not be unwise to continue talks with China, it will not be prudent either to give up on U.S. and European nations without determining the endgames and implications of these summits for something, historically speaking, as fickle as the Sino-Indian relations.

As for the immediate neighbor of both China and India, the Pakistani military that has always prevented its elected government from scaling up trade with India unless New Delhi engages with it on Kashmir and which Modi has flatly refused, the Chinese admonition a few days prior to the Wuhan summit to quell tensions in its relations with New Delhi must have added to the sense of unease, “isolation” and reflection on perils of relying on a single strategic power, by watching the close camaraderie between Modi and Xi.

Understandably, Pakistan that is hugely obliged to China for boosting its confrontation with India by enabling its strategic program in terms of transfer of nuclear weapons and ballistic missile technology from 1989 to 1992, protecting it from multilateral moves to punish it for harboring terrorists, and now gaining from the Belt and Road Initiative and the CPEC “investments” (debts in real sense) has no option but to swallow the bitter pill and end its negative raison-d’etre if it can.