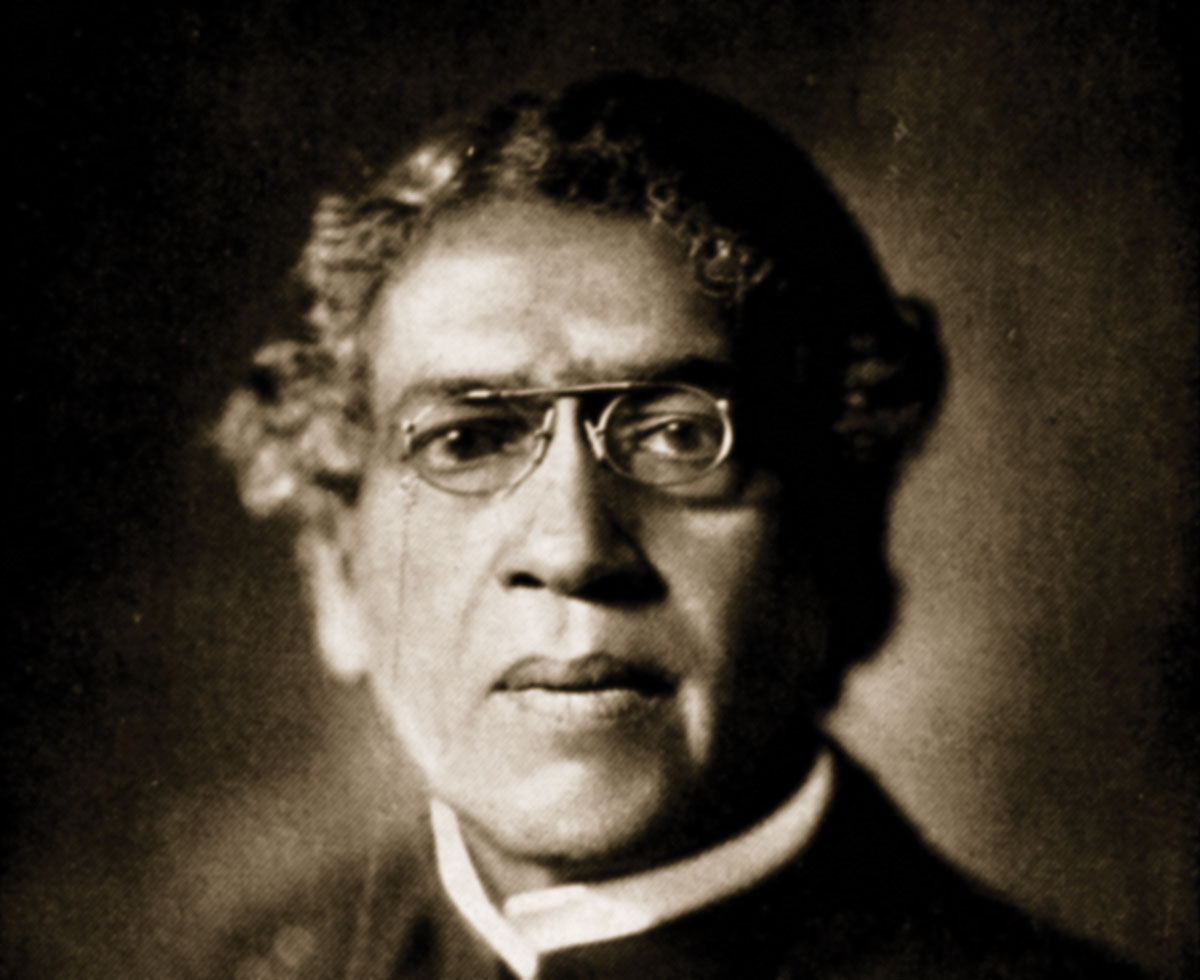

PIONEERING SCIENTIST, PRINCIPLED MAN: SIR JAGADISH CHANDRA BOSE (1858- 1937)

Photograph of Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose in a biography by Patrick Geddes published in 1920. (Wikimedia Commons)

November 30 was the 158th birth anniversary of India’s pioneering scientist Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose. Ashfaque Swapan offers a tribute to this remarkable man and scientist. – @siliconeer #siliconeer #SirJCBose #Tribute #Science #GalenaDetector #PhotovoltaicCell #Semiconductor #India #BoseInstitute #Microwave #HertzionWaves

Lord Kelvin wrote in 1896 that he was: “literally filled with wonder and admiration: allow me to ask you to accept my congratulations for so much success in the difficult and novel experimental problems you have attacked.”

His Galena Detector was the first semiconductor device and the earliest photovoltaic cell (U.S. patent granted in 1904). The U.S.-based Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineer recognizes Bose as one of the pioneers in the discovery of radio.

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, India’s first modern scientist, was dedicated to scientific research, but was loathe to patent his many innovations. Upright and principled, he protested racial wage discrimination by refusing to accept a salary for three years, and when authorities balked at providing resources to build a laboratory, he used his own resources and own time left after teaching for long hours, to do cutting-edge research that broke the myth in the West that Indians were incapable of excelling in scientific research. In 1917, he founded Bose Institute, India’s first modern scientific research center.

According to the Bose Institute, his scientific investigations can be broadly divided into the following periods:

During 1894-1899, Bose started experimental research on the Hertzion waves (1894) in India and created the shortest radio-waves (5mm). He had devised a portable (10″ x 12″) apparatus for the study of optical properties of 5 mm waves. It had the earliest waveguide and Horn Antenna of Microwave engineering of today.

His Galena Detector was the first semiconductor device and the earliest photovoltaic cell (U.S. patent granted in 1904). The U.S.-based Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineer recognizes Bose as one of the pioneers in the discovery of radio.

During 1899-1902, Bose initiated detailed study of coherer leading to his discovery of the common nature of electric response to all forms of stimulation, in animal and plant tissues as well as in some inorganic models

During 1902-1907 he continued efforts to devise inorganic models of the biophysical phenomena underlying electrical and mechanical responses to stimulation, the transmission of excitation in plant and animal tissues and of vision and memory.

During 1907-1933 he devoted himself mainly to the study of response phenomena in plants, complexity of whose responses lies intermediate between those of inorganic matter and animal.

Echoes of the exemplary values of Bose come from his remarkable father, Bhagwan. As a deputy magistrate in colonial India, he had an exalted position – but he sent the young Jagadish to a pathshala or village school, rather than an English school, to develop the impressionable young boy’s ties with his ancestral roots.

It worked. Jagadish grew up with fond memories of Muslim and Hindu peasant kids as his friends. It was a time that inspired his wonder about nature, flora and fauna – something that would cause a pivotal turn in his scientific investigations in later life. Only when he was 9 was Jagadish sent to an English school.

It was in Kolkata’s St. Xavier’s College that Jagadish was drawn to physics, thanks to the legendary professor of physics Father Lamont.

Jagadish went to England and entered Christ College at the University of Cambridge in 1881. He eventually got a degree from Cambridge as well as London.

Jagadish returned to India when he was 25, raring to go. At that time, the British Raj reigned supreme. It was a time of British racial prejudice. Indians could enter the ICS as equals as long as they passed the exam, but the Imperial Education Service was by nomination only. It was virtually off limits for Indians, even for those with top European qualifications. Indians were shunted off to the less prestigious Provincial Service, where they did the same work for lesser pay.

Jagadish was fortunate to get the support of Lord Ripon, the Indian Viceroy, who nominated him for the Imperial Service, but the Director of Public Instruction in Bengal was not keen. Ultimately Jagadish was offered a temporary position as physics professor of Presidency College.

Such was the prejudice against an Indian taking an important position of science in the Education Department that when Jagadish was made Officiating Professor of Physics at Presidency College, the principal protested the appointment.

Since it was a temporary appointment, his pay was a third of what British professors made. In protest, Jagadish refused to accept his salary. Despite acute financial hardship, Jagadish refused to accept a paycheck for three years.

That did not mean he neglected his work at Presidency College. Jagadish was a huge and immediate success as a teacher. The daily roll became superfluous, students struggled for front seats for a better view of his experiments.

After three years, both the principal C.H. Tawney and Director of Public Instruction Sir Alfred Croft realized the value of his work and became his staunch friends. By a special order of the director, his job was not only made permanent, but with retrospective effect. He received full pay for last three years, most of which went towards paying his father’s debt.

On his 35th birthday, Nov. 30, 1894 he resolved that his life will be dedicated to the pursuit of new knowledge. His biographer Patrick Geddes writes: “Within three months of this resolve, with no laboratory to speak of, and with the help of an untrained tinsmith, he was able to devise and construct new apparatus for his first research on some of the most difficult problems of electric radiation. Success was immediate; and in the course of a year the Royal Society undertook the publication of his investigations, and offered help from their parliamentary grant for their continuation.”

The University of London gave him a Doctorate of Science without examination. Lord Kelvin wrote in 1896 that he was: “literally filled with wonder and admiration: allow me to ask you to accept my congratulations for so much success in the difficult and novel experimental problems you have attacked.” Famed physicist M. Cornu, former president of the French Academy of Sciences wrote in 1897 “the very first results of your researches testify to your power of furthering the progress of science.”

He now had a dream of establishing an institute of science, but the Education Department refused to help. Undaunted, he founded the first modern scientific research institute in India in Kolkata in 1917.