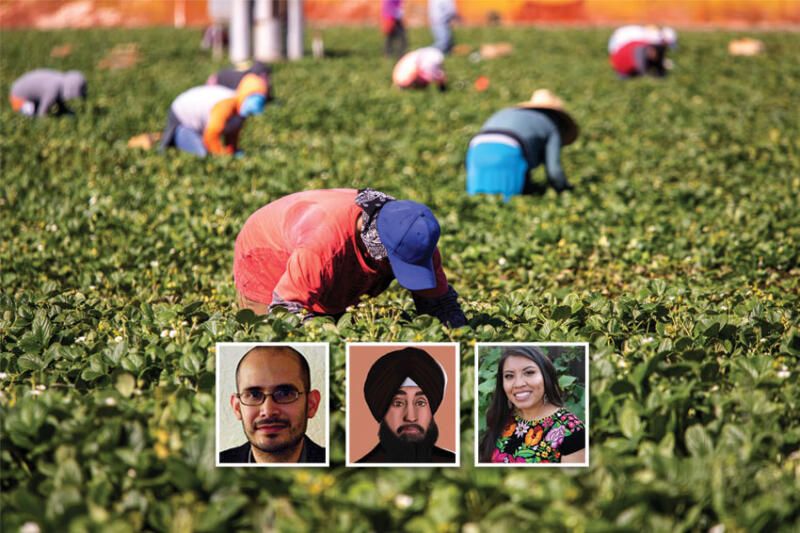

Kern County, Calif. Farmworkers, Food Processors, Face Covid-19 Vaccination Barriers

(Above, Inset: l-r): Edward Flores, Assistant Professor of Sociology and co-director of the UC Merced Center on Labor and Community; Naindeep Singh, Jakara Movement (impact for Punjabi food processors); and Sarait Martinez, Executive Director, Centro Binacional. (Siliconeer/EMS)

At an Ethnic Media Services briefing, Oct. 20, with support from the Sierra Health Foundation and the California Department of Public Health, speakers – Edward Flores, Assistant Professor of Sociology and co-director of the UC Merced Center on Labor and Community; Juana Montoya, Lideres Campesinas community organizer: pandemic impact and vaccine access for women farmworkers; Margarita Ramirez, Centro Binacional Mixtec community worker (impact & vaccine access for Mixtec and other indigenous agricultural workers; Naindeep Singh, Jakara Movement (impact for Punjabi food processors); and Sarait Martinez, Executive Director, Centro Binacional – talk about COVID vaccination rates and the challenges faced in vaccinating agricultural workers in Kern County, in Calfornia.

Anna Padilla at the UC Merced, Center for Labor and Community, helped in organizing this briefing.

Professor Ed Flores shared data on low vaccination rates among agricultural workers and those experiencing risks of the eviction, food insecurity, and lack of health insurance in Kern County and the Central Valley.

The Central Valley was a hot spot for a COVID spread in 2020. Agricultural workers experienced a much higher risk of pandemic related death in 2020 compared with other workers.

Current agricultural workers are particularly disadvantaged, and U.S. agricultural workers still have the lowest rates of vaccination. “This is really not necessarily the problem in itself, this is just a symptom of the problem because when we look at the household pulse survey, it tells us that the rates of vaccination are lowest among those persons that are lacking health care and that are experiencing housing and food insecurity,” said Dr Flores.

“When we see low rates of vaccination among agricultural workers, this is really a symptom of a much deeper problem that has to do with lacking health care and experiencing housing and food and security and often, it’s just by sharing some of our center’s recommendations to focus on increasing the safety net, particularly for those most disadvantaged groups. The Central Valley had among the state’s highest increase in deaths between 2019 and 2020,” said Dr Flores.

“The Central Valley has a very young population, the lowest median age, and the largest share of its population, that are children, compared to the other 10 regions in California. It was still near the top and the highest increase in deaths from 2019 to 2020. Los Angeles, the Inland Empire, and the Central Valley had by far, the highest increase in death between 2019 and 2020.

“The difference between the Central Valley and Los Angeles and the Inland Empire is not as great as it would appear just because the Central Valley has the state’s youngest population and we saw fewer pandemic-related deaths among younger populations, so there’s quite a bit of parity between Los Angeles and the Inland Empire and the Central Valley.

“When we look specifically at counties, we see that of those 12 counties with the highest increase in death between 2019 and 2020, eight of those 12 counties were in the Central Valley. Kern County had a 23.5% increase in death between 2019 and 2020. There were 1,230 pandemic-related deaths, we are estimating between March and December in 2020,” said Dr Flores.

“Our fact sheet, that was released in April 2021, suggested that worker deaths accounted for over one-fourth of the state’s pandemic-related deaths. In California, agricultural workers had the second highest rate of pandemic-related deaths, second only to warehouse workers, and this is in line with some other research that shows high rates of death among agricultural workers from UC San Francisco,” said Dr Flores.

Workers in Kern County had a 37% increase in death between 2019 and 2020. Those workers worked in the top 10 highest risk industries, agriculture, and nine other industries had a 37 percent increase in death,” said Dr Flores.

“Among workers and high-risk industries, there’s a high probability of being immigrant and non-citizen; earning low wages; living in large households that have children; renting and being poor; but yet there’s still some very significant differences between agricultural workers and other high-risk workers, because of the amount of inequality that we see with with agricultural workers,” pointed Dr Flores.

“Agricultural workers still have the lowest vaccination rates among all other essential workers. By far, according to the Youth Census Bureau, only 50 percent of agricultural workers nationally have been vaccinated, and this is much lower than any other essential group or non-essential workers who have an 84% vaccination rate.

Vaccination rates varied by household food sufficiency, people living in households that had enough of the kinds of food that they wanted to eat, had vaccination rates of 88%. An inverse relationship to food sufficiency and vaccination rates was seen for those who lived in households where there was often not enough to eat. The vaccination rates averaged at 56 percent,” said Dr Flores.

“To improve vaccination rates and reduce the spread of COVID, there needs to be greater investment in expanding the safety net, and some of these provisions might consist of wage replacement for undocumented immigrants; extending paid emergency sick leave; and Improving the distribution of rental assistance to renters who are at risk of eviction,” said Dr Flores.

The major ways in which agricultural workers are more disadvantaged than other workers:

- 67 percent of agricultural workers are non-citizen;

- their median salary and wages are $14,000 per year;

- 34 percent live in households that are below the poverty line;

“Typically, farmworkers live and learn in overcrowded households with many workers and there’s one out of every five households as a multiple family household. The American Community Survey does not even collect worker data on people living in group quarters so those agricultural workers who live in labor camps are even far more disadvantaged than the profile that we have from the ACS,” said Dr Flores.

Juana Montoya, a community outreach worker in Kern County for Lideres Campesinas, the largest association of farmworker women in the state, described a day in the life of a farmworker woman, where just having enough time in the day to figure out how to get vaccines is a major challenge.

“Working conditions in the field are not the best. The heat during the summer made me sick a few times and the winter felt so cold, working outdoors a year ago, during the pandemic, I was working in a cold storage, repacking grapes that were going to be shipped to Australia.

“My husband, also being a farmworker, and I, would start our day at 4 30 a.m. Together we would pack our lunch and get our two children ready and wait outside our home for our transportation to arrive. A great fear I always had was having to carpool to our working site and not knowing if anyone in the vehicle was infected with COVID. This is a schedule every farm working family has, and what they go through, every day,” said Montoya.

“About the vaccine, when we are educating the community, we tell them there is no chip to track them, there is no negative effect, you don’t lose your fertility, and we create a trust with them and many of them who have told us that after hearing us giving them the information they will get vaccinated.

“Immigration status is also why many have not gotten the vaccine. Not having legal documents and hearing the word ‘registration,’ there’s going to be distrust and fear of giving personal information to the government.

“Many don’t have internet access and are not familiar with navigating the internet. Language barriers and reliable transportation are also among the list,” said Montoya.

We work with the United Against COVID Coalition in Kern, California Worker Outreach Project or C-WOP. We also work with the public health institute together towards health campaign among others. Other projects and initiatives and being at work and far from home there is no way to stop working and make a phone call to 2-1-1 or to the department of human resources sometimes there’s no reception while working in the fields so ‘taking it to the field’ initiative has been amazing and successful,” said Montoya.

“The best approach to expand vaccine is bringing education and vaccines right to the community. We knew Kern County was among the hardest counties being hit, and trusted messengers from community-based organizations are highly needed and necessary for battling misinformation and fears,” said Montoya.

“Among the fears, was being deemed a public charge, was not having health care coverage, and going into depth the fear of immigration, the fear of dying. Every day, farmworkers face resource barriers that prevent them from accessing much needed government assistance and information. As a community-based organization and part of different coalitions addressing the pandemic, we have noticed that long-standing issues due to inequities must change in Kern County,” said Montoya.

“We know that indigenous language speaking communities in California at about a quarter of all Campesinos in the state, with significant concentrations in the Central and Central Coast and San Joaquin Valley. Our ancestors had very complex societies, with highly sophisticated understanding and practices of agriculture, mathematics, astronomy, cosmology, and in others. Indigenous campesinos have a deep respect for, and knowledge of the land. We’re really the experts in agriculture and food production. It’s really rooted in our ancestral, and sustainable agricultural practices. That carries this multi-billion-dollar agriculture economy in the state,” said Dr Sarah Martinez.

“The thing that really limits the access to our community is the language. In the lack of information and the fact that many times when new message comes out, it is usually translated from English to Spanish, but those same concepts many times do not exist in our communities. Finding the right terminology, and how do we explain things, is it’s completely different. Many indigenous campesinos speak Spanish as a second language, but the vast majority are monolingual in their indigenous languages,” said Dr Martinez.

“There’s a lot of anxiety and stress over really rising causes such as the basic needs like paying for housing; for the food; for childcare; for all the bills; there was a big fear of contracting COVID 19; and to really spreading it to the children and their families because of the overcrowded housing.

“The fear of taking time off because not having the means to take sick time, and a lot of misinformation on who can take sick time, there was a deep concern from parents about the emotional well-being of their kids and how that will impact their academic progress and how older parents weren’t really equipped because many of our indigenous farm workers do not have a formal schooling. Reading and writing sometimes could be a limit for our communities as well. Most of those were some of the kind of findings,” said Dr Martinez.

Naindeep Singh is a co-founder of the Jakara Movement. He is also a member of the Fresno County School District Board. Singh talked about the presence of Punjabis in the food processing plants, particularly in Kern and the Central Valley.

“The Punjabi community dates back, at least the agricultural sector in Kern County, over a hundred years. It’s fast beginning to change where more often than not, younger workers do not prefer to go into farm working. Certain special category – elderly immigrants still go into farm work. Although, they’re not alone, a lot of young women, and a lot of undocumented community members work at various food plants as well,” said Singh.

“How the pandemic has most impacted them – At least in Kern County, it has been a patchwork. The single biggest factor at the macro level has been what the employer has done. In some of the larger plants it has been tied to fear for labor shortages than necessarily the welfare of their workers. But those that have created situations, in some ways almost even have mandated vaccinations, have had a high uptake, and those include some of at least the Punjabi families that we work with,” said Singh.

“It is very different, especially at some of the smaller food processing companies, and even some of the smaller agricultural production agencies. Some of them, for political reasons, for various reasons, have adamantly actually not made the vaccination available,” said Singh.

“We’ve heard numerous cases where that has been the case. For a farmworker, or even a food process worker, to make time in a schedule that does not really permit that, it becomes all the more cumbersome. I think a mandate has to go in tandem with in-language education and outreach which there are coalitions in Kern County, that have been really at the front lines, making sure that is happening,” said Singh.

Addressing the big issue now, vaccinating children, what is the most effective thing we could do, given the need for stronger support systems, given the isolation, the lack of transportation? How can we make a breakthrough on the vaccination of the children of these essential workers in both the fields and the food processing plants?

“My only suggestion would be that in thinking of devising the mechanisms for making COVID vaccinations accessible to children, we should really have deep conversations with those organizations like the ones that are on the call today, to learn about on the grounds, how such outreach would be most effective,” said Dr Flores.

How much do you see hesitancy around vaccinating children? How do we overcome that? How do we help expand the access for kids?

“Many of the farmworkers who are vaccinated, are excited to vaccinate their child, because they want their child to be safe, but on the other hand, the farmworkers that are not vaccinated and that that are not planning to get their vaccine, they want to wait and don’t want to get their child vaccinated. Some comments we have heard – ‘If I’m not going to get vaccinated, neither is my child.’ ‘I don’t want to put my child at risk.’

“I think just continuing our efforts that we’re doing now in educating our communities about the importance of this vaccine, hopefully, helps them and makes them see this differently, and change their mind, said Montoya.

On the children of Punjabi workers in the agricultural sector, what are your thoughts? Are you optimistic? Do you have any special recommendations over and above the mandate for employers?

“I’m extremely optimistic. I think with the availability, and in the push, especially at the school level. Although, it’s been sort of uneven in different parts of Kern County, but I think, there’s less trepidation for children and some of the other sort of narratives and discourse that we’ve heard about fear for this amongst children, at least even in the misinformation I’ve heard, it’s actually never really been centered around children. It’s been much more about around maybe sterility and other sort of birth complications, but the information has not been centered around adverse effects on children,” said Singh.