India’s #MeToo Movement: An Explosive Revolution for Gender Parity

Tanushree Dutta talks during an interview with an Indian media outlet in Mumbai, Oct. 12, 2018. The year-old #MeToo movement has finally gathered steam in India in recent days with Bollywood figures, a government minister, several comedians and top journalists among those accused of abusing their positions to behave improperly towards women. The spark was Hindi film actress Tanushree Dutta, who in a recent interview accused well-known Bollywood actor Nana Patekar of inappropriate behavior on a film set 10 years ago. He denies the allegations. (Sujit Jaiswal/AFP/Getty Images)

India has been shaken to its core by the sudden wave of the #MeToo movement that started with the recounting of the decade-old saga of sexual harassment faced by visiting U.S.-based Tanushree Dutta, also a former Miss India and Indian film actor, writes Priyanka Bhardwaj.

Replying to a query as to why she had disappeared from the industry, Dutta detailed her frightening ordeal, as can be seen in numerous videos thronging the YouTube and also corroborated by many eyewitnesses, of harassment by co-actor, Nana Patekar, on the sets of the movie, and her prior similar experience with the film maker Vivek Agnihotri of “Chocolate.”

As her shocking statements elicited immense controversy, support and criticism other industry-persons and the public, it also set off a series of complaints of torment by women belonging to the fields of journalism, entertainment, the arts and advertising, politics, sports, literature, and other walks of life, at the hands of men, belonging to the higher echelons of power, influence and resource, who harbored no fear of punishment, and their years’ of silence on their tales of trauma.

The hashtag movement turned into a rallying cry against all forms of violence and harassment faced by women in the work place.

Prominent names started getting called out have been senior journalists, Vinod Dua, C. Gauridasan Nair, Gautam Adhikari, Fahad Shah, K.R. Sreenivas, Mayank Jain, Prashant Jha, and Satadru Ojha; Padma awardee and celebrated painter, Jatin Das; film makers & directors, Vikas Bahl, Subhash Ghai, Sajid Khan and Sham Kaushal; actors, Alok Nath, Rajat Kapoor, Piyush Mishra and Zulfi Syed; authors, Chetan Bhagat and Sachin Garg; music director, Anu Malik; lyricist, Vairamuthu; singers, Abhijeet Bhattacharya, Kailash Kher and Raghu Dixit; Head of Indian National Congress Youth wing; standup comedians, Utsav Chakraborty, Aditi Mittal, Gursimran Khamba and Kanan Gill; BCCL CEO, Rahul Johri; Yash Raj Films’ VP, Ashish Patil; Content Studio Head at Reliance; Ajit Thakur, Chief of Corporate Communications at Tata Motors, Suresh Rangarajan; and Ad-man and consultant Suhel Seth, to name a few.

This list of alleged predators has only been growing with the passing of each day and has led to resignations in the world of media and advertising and closure of a famous film company, besides ostracism of many professionals within their industries.

The accusations betray a clear pattern and modus operandi of molestation adopted by most predators, though their reactions to their individual allegations has been in variance, from denials to tendering public apologies, resignations, counterattacks and filing of defamation lawsuits against the supposed victims.

The largest milestone so far achieved by this movement that was earlier believed to be limited to the film and media industries has touched the political class like never before.

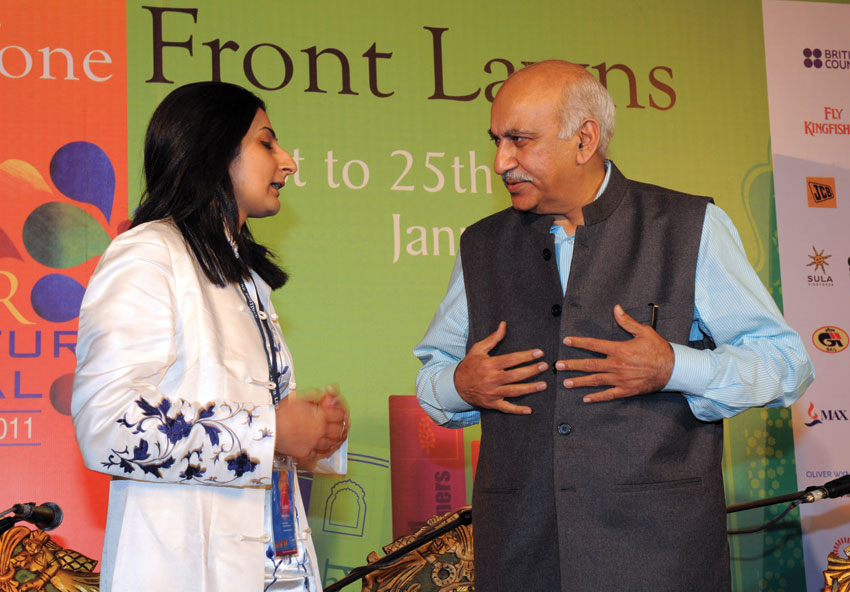

Despite the initial brazing it out, with the filing of a lawsuit of defamation against one of his accusers, Priya Ramani, the Minister of State for External Affairs, M.J. Akbar, was forced to quit due to mounting public pressure.

Ramani was the first journalist to have publicly accused him of harassment when he was the editor of a prominent newspaper, Asian Age, in the early 1990s, and she a young trainee, and then the coming out of 20 more women against Akbar decimated his high-profile public outing.

What angered and disgusted the public at large was the silence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who faces re-election in 2019, and Akbar’s immediate superior, Sushma Swaraj, herself the woman Union Minister of Foreign Affairs, who lead a government that hails itself the champion of women, what with its freshly minted social welfare programs and slogans of “beti bachao, beti padhao’ (save the girl child, educate her), and abolition of the Triple Talaq(a way by which Muslim men unilaterally divorced their wives by simple uttering, texting or telephoning the word ‘Talaq’ thrice).

On two more counts Akbar’s case will be significant; firstly, the way it plays out in the court of law, it will be minutely scrutinized to see what precedents it sets in the fight for justice and gender parity, and secondly, the collective letter written by the group of women victims unmasks the clear picture of casual misogyny, entitlement and sexual predation that the former editor boss employed and is often the case with other predators as well in the Indian work space.

Though this movement has drawn its share of criticism over probable instances of false allegations due to bypassing of verification of allegations in the short term, and other such remarks that the movement will die down as it will not be able to withstand the backlash of patriarchy, the truth remains that Indian women had been suffering for far too long for want of closure, solidarity and empathy.

Undeniable the year-old U.S. #MeToo movement and U.S. law student, Raya Sarkar’s crowd-sourced list of named and accused by anonymous victims raised the urge of Indian women-sufferers to “call out” on social media available for all, once Dutta’s story ignited that fire simmering within them.

If figures are anything to go by, the country has not seen any rise in women in the work force despite the growth in their education rates over the past decades.

In 1990, 34.8% women accounted for the labor force in India, but by 2016, their proportion plunged to 23.7% states a World Bank report.

Another official account shows that between 2014 and 2017 there has been 54% increase in registered cases of sexual harassment at workplace – which translates into nearly two cases reported every day.

It is no secret that in most cases when it becomes exceedingly becomes difficult for a woman to work, she takes to her full-time domestic status, thus compromising the nation’s GDP.

Since the allegation against its Minister became a political issue, the incumbent government has woken up to weighing proposals to tighten sexual harassment laws to bring in processes to verify complaints, legitimize them and then follow them through to their logical conclusion.

It was in 2013 that the previous government had enacted the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act.

But compliance issues plague the enactment of this Act as well as the preceding Visakha Guidelines that mandates companies with more than ten employees to set up an internal complaints committee for women.

Besides, there are anomalies and loopholes that demand immediate amendments, such as the provision of filing a complaint within three months that needs to be made more flexible, given the nature of impact sexual crimes have on the victims; the question of who ensures compliance at the workplace and is liable if the provisions of law are not followed; and issues of women who work in companies of smaller size and thereby escape the provisions of current laws.

Legal experts and activists also rue the fact that the existing system takes too long to allow for any motivation among women to report their cases with the police, the case in point being the non-outcome of the case of rape filed against the former Tehelkaeditor Tarun Tejpal since 2013.

It is, however, certain that benefits in the long term will accrue, as sexual harassments at workplaces will no more be condoned as before, and with inclusion of rural women force in this movement, as planned by many gender activists, and sharpening of legal instruments companies will be forced and propelled towards prioritizing improvement of their work places which in turn will only upgrade their credibility and profits.

The hope for the restorative power of the system of justice to bring in the balance of gender parity has made the Indian women so sure for the first time.