HOW INDIA SLAMMED INTO EURASIA

Did you know India was not a part of Asia originally? India set a continental speed record as it crashed into Eurasia 80 million years ago due to a double subduction, a new MIT study has found. A PTI report.

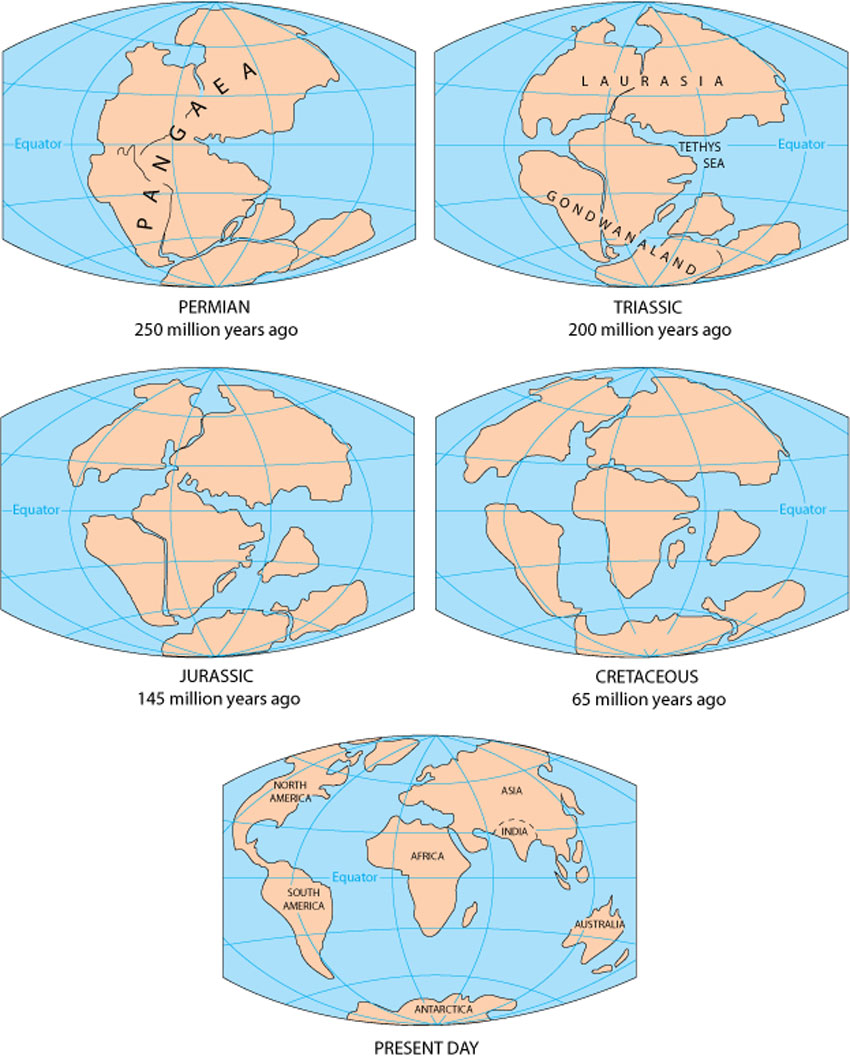

In the history of continental drift, India has been a mysterious record-holder, researchers said. More than 140 million years ago, India was part of an immense super-continent called Gondwana, which covered much of the Southern Hemisphere.

Around 120 million years ago, what is now India, broke off and started slowly migrating north, at about 5 centimeters per year. Then, about 80 million years ago, the continent suddenly sped up, racing north at about 15 centimeters per year – about twice as fast as the fastest modern tectonic drift.

The continent collided with Eurasia about 50 million years ago, giving rise to the Himalayas.

For years, scientists have struggled to explain how India could have drifted northward so quickly.

Now geologists at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have found India was pulled northward by the combination of two subduction zones – regions in the Earth’s mantle where the edge of one tectonic plate sinks under another plate.

As one plate sinks, it pulls along any connected landmasses, according to the study published just days after a devastating 7.9 magnitude earthquake hit Nepal.

The geologists reasoned that two such sinking plates would provide twice the pulling power, doubling India’s drift velocity.

The team found relics of what may have been two subduction zones by sampling and dating rocks from the Himalayan region.

They then developed a model for a double subduction system, and determined that India’s ancient drift velocity could have depended on two factors within the system: the width of the subducting plates, and the distance between them.

If the plates are relatively narrow and far apart, they would likely cause India to drift at a faster rate, researchers said.

The group incorporated the measurements they obtained from the Himalayas into their new model, and found that a double subduction system may indeed have driven India to drift at high speed toward Eurasia some 80 million years ago.

“In Earth science, it’s hard to be completely sure of anything,” said Leigh Royden, a professor of geology and geophysics in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences.

“But there are so many pieces of evidence that all fit together here that we’re pretty convinced,” said Royden.

Based on the geologic record, India’s migration appears to have started about 120 million years ago, when Gondwana began to break apart.

“When you look at simulations of Gondwana breaking up, the plates kind of start to move, and then India comes slowly off of Antarctica, and suddenly it just zooms across – it’s very dramatic,” Royden said.

Based on the geologic record, India’s migration appears to have started about 120 million years ago, when Gondwana began to break apart.

India was sent adrift across what was then the Tethys Ocean – an immense body of water that separated Gondwana from Eurasia.

In 2013, the team, along with 30 students, trekked through the Himalayas, where they collected rocks and took paleomagnetic measurements to determine where the rocks originally formed.

From the data, the researchers determined that about 80 million years ago, an arc of volcanoes formed near the equator, which was then in the middle of the Tethys Ocean.

A volcanic arc is typically a sign of a subduction zone, and the group identified a second volcanic arc south of the first, near where India first began to break away from Gondwana.

The data suggested that there may have been two subducting plates: a northern oceanic plate, and a southern tectonic plate that carried India.

The research was published in the journal Nature Geoscience.