Harvard students’ site helping Ukraine refugees find housing

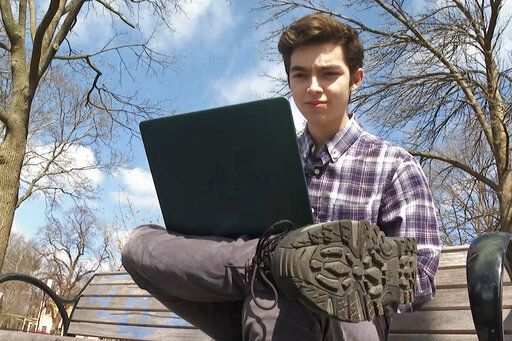

Harvard freshman Marco Burstein, 18, of Los Angeles, works on his computer near the campus of Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., March 16, 2022. Moved by the plight of Ukrainian refugees desperate to escape Russian bombardment across the former Soviet republic, Burstein and classmate Avi Schiffman, of Seattle, used their coding skills to create UkraineTakeShelter.com over three frenzied days in early March. (AP Photo/Rodrique Ngowi)

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (AP) — Two Harvard University freshmen have launched a website designed to connect people fleeing Ukraine to those in safer countries willing to take them in — and it’s generating offers of help and housing worldwide.

Moved by the plight of Ukrainian refugees desperate to escape Russian bombardment across the former Soviet republic, Marco Burstein, 18, of Los Angeles, and Avi Schiffman, 19, of Seattle, used their coding skills to create UkraineTakeShelter.com over three frenzied days in early March.

Since then, more than 18,000 prospective hosts have signed up on the site to offer assistance to refugees seeking matches with hosts in their preferred or convenient locations. On a recent day, Burstein and Schiffman logged 800,000 users.

“We’ve heard all sorts of amazing stories of hosts and refugees getting connected all over the world,” Burstein said in an interview on the Harvard campus. “We have hosts in almost any country you can imagine from Hungary and Romania and Poland to Canada to Australia. And we’ve been really blown away by the response.”

Five weeks into the invasion that has left thousands dead on both sides, the number of Ukrainians fleeing the country topped a staggering 4 million, half of them children, according to the United Nations.

Schiffman, who’s been taking a semester off to work on several projects, said from Miami he was inspired to use his internet activism to help after attending a pro-Ukraine rally in San Diego.

“I felt that I could really do something on a more global scale here,” he said. “Ukraine Take Shelter puts the power back into the hands of the refugee … they’re able to take the initiative and find the listings and get in contact with hosts by themselves instead of having to freeze on a curb in Eastern Europe in the wintertime.”

Among those who have taken in refugees through the website is Rickard Mijarov, a resident of the southwestern Swedish city of Linkoping who’s sharing his home with 45-year-old Ukrainian evacuee Oksana Frantseva, her 18-year-old daughter and their cat.

Mijarov and his wife signed up at an embassy indicating they’d help, but then stumbled upon the Harvard students’ site and registered there as well.

“The next morning, I had a message from Oksana asking if we had place for them,” he said in an interview via Zoom. “It became reality quite fast.”

“I was surprised how quickly Rickard answered to me,” Frantseva said in halting English. Five days later, she, her daughter and their pet were at the front door.

Burstein and Schiffman designed the platform with combat refugees’ particular concerns in mind. They worked to make it as easy to use as possible so someone in immediate danger can enter their location and see the offers of help that are closest to them.

On the hosting side, they also gave prospective hosts the opportunity to indicate what languages they speak; how many refugees they can accommodate; and any restrictions on taking in young children or pets.

To help avoid human trafficking and other hazards that vulnerable refugees face, the platform encourages evacuees to ask hosts to provide their full names and social media profiles, and request a video call to show what accommodations they’re offering.

“We know that this is potentially a dangerous situation, so we have a lot of steps in place to ensure the protection of our refugees,” Burstein said. “We have a detailed guide that we give to all refugees to help them verify the host that they’re talking to — make sure that the person that they may be speaking with on the phone is the same one that they’re meeting up with in person.”

The two students say they’re trying to arrange a meeting with officials from the U.N. refugee agency, and they are also looking to work with Airbnb, Vrbo and other online vacation rental companies.

So far, they’ve borne all the expenses — a hardship for college students — for web hosting and Google Translate costs. But they’re determined to continue as long as possible and are looking into registering as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit so they can apply for grants.

Back in Sweden, Mijarov admits it was a bit unnerving to open his home, but he has no regrets.

“It’s the first time we are doing something like this,” he said, seated next to Frantseva. “But they’re very nice people. So, yeah, going along well.”

___

Follow Rodrique Ngowi on Twitter at https://twitter.com/ngowi

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.