Fetterman harnesses power of social media in Senate campaign

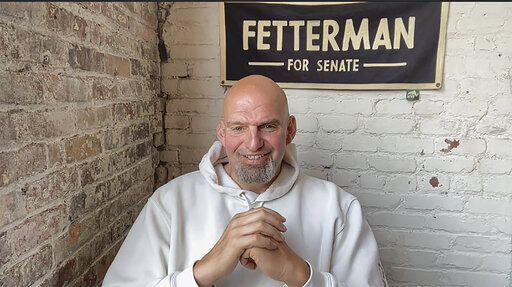

FILE – Pennsylvania Lt. Gov. John Fetterman, the Democratic candidate for the Pennsylvania Senate seat, speaks during a video interview from his home in Braddock, Pa., July 20, 2022. (Julian Routh/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette via AP, File)

HARRISBURG, Pa. (AP) — In one of this year’s most competitive U.S. Senate races, the biggest moments aren’t playing out on the campaign trail. They’re unfolding on social media.

For one stunt, Democrat John Fetterman of Pennsylvania rolled out an online petition to get his Republican rival, celebrity heart surgeon Dr. Mehmet Oz, enshrined in New Jersey’s Hall of Fame — a nod to Oz moving from his longtime home in New Jersey to run in neighboring Pennsylvania.

For another, Fetterman paid $2,000 for an airplane to haul a banner over weekend beachgoers on the Jersey Shore welcoming Oz back home to the Garden State. And in particularly viral posts, Nicole “Snooki” Polizzi, star of the infamous MTV show “Jersey Shore,” and “Little” Steven Van Zandt of “The Sopranos” and Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band recorded videos telling Oz to come home.

“Nobody wants to see you get embarrassed,” Van Zandt says. “So come on back to Jersey where you belong.”

For a campaign that could ultimately cost more than $100 million, the stunts are cheap ways for Fetterman, Pennsylvania’s lieutenant governor, to generate attention. The millions of views are helpful for a candidate who has largely been sidelined from personal appearances after suffering a stroke in May.

And it’s about more than getting laughs: The social media strategy could prove potent in defining Oz as a carpetbagger disconnected from the state’s residents and culture.

“The reason it stands out is he seems to be doing the best job of anyone this election cycle at contrasting his personality versus that of his opponent,” said Dante Atkins, a Democratic campaign strategist based in Washington, D.C., who has not done any work for Fetterman.

Republicans acknowledge that Fetterman’s social media game is top-notch. But they question the value. Even at a time when most Americans use social media, many Pennsylvania voters on social media don’t see Fetterman’s material and, anyway, elections aren’t about who’s got the best troll game, they say.

Republicans also argue that Fetterman’s greatest hits are missing the issues that voters are most likely to consider when making up their minds: inflation, gas prices and the economy, for instance.

“People don’t really care where I’m from,” Oz said in an interview. “They care what I stand for.”

A lot of the material comes from Fetterman himself, said campaign spokesperson Joe Calvello. He does a lot of the posting on Twitter and if Fetterman himself doesn’t post it, he helps originate ideas.

He’ll shoot texts to campaign staff saying, “‘Hey what about this,’ or ‘did you see this,’” Calvello said. “He’s still very involved.”

Other material comes from campaign staff who develop ideas that stay on-brand for Fetterman and on turf that the candidate has staked out, Calvello said. That includes accusing oil companies of jacking up gas prices.

The concept of trolling Oz, and a lot of the memes, also came from Fetterman, Calvello said. The idea for the video by Snooki emerged from a brainstorm by a couple members of the staff, Calvello said.

Campaign staff wrote the script and Snooki — who was paid less than $400 through the video-sharing Cameo website — ad-libbed some of it, but was not in on the joke until afterward.

With 3.2 million views, it scored the most engagement on Twitter ever on Fetterman’s account, “and that’s a high bar,” Calvello said.

Van Zandt did his video for free and ad-libbed his script after the campaign contacted him directly to see if he’d cooperate, Calvello said.

It is difficult to know how much this will help Fetterman in a year when Democrats face stiff political headwinds, including high inflation and a traditional mid-term backlash against the party of the president.

Political scientists have had a hard time isolating the forces that affect how voters make up their minds, said Christopher Borick, an assistant professor of political science at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

In addition, voters tend to be older than the average social media user, Borick said.

Still, Pew Research Center last year estimated that seven in 10 Americans use social media, and it is unquestionable that the medium is becoming more important to reaching voters.

“The proof in the pudding is that campaigns have increasingly turned to it, and so they’re going on the belief that it is a necessary and key component,” Borick said.

Maggie McDonald, a post-doctoral fellow who studies social media in congressional campaigns at New York University’s Center for Social Media and Politics, said Fetterman’s social media game is among the best, if not the best, she’s seen.

“I imagine in future years people will try to emulate this,” McDonald said.

In addition to making people laugh, she said she thinks Fetterman’s stunts could motivate appreciative viewers to contribute money to his campaign and push apathetic Democrats to get off the sidelines to vote for him.

Oz has tried to harness the power of social media for his campaign, and tried to respond to Fetterman online. He has drawn particular focus to Fetterman’s absence from traditional retail campaigning in the aftermath of his stroke, including using a meme from the TV series “Lost.”

In response to a Fetterman tweet about high gas prices, Oz retorted, “Curious as to why you have to fill up your tank so often when you’re not out on the campaign trail meeting with Pennsylvanians.”

Fetterman responded, “Dude, you’re literally from Jersey,” before he referred to a New Jersey state law that requires gas station attendants to pump gas for motorists. “I bet you don’t even know how to pump your own gas.”

Fetterman’s campaign argues that its trolling of Oz is on point with issues that matter to voters. Some elements of it — such as a “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” parody video — try to ask whether a man who is worth nine figures can advocate for regular people who are pinched by high gas prices.

Besides contrasting himself with Oz, Fetterman is well versed in internet culture.

“He’s extremely online, he knows his memes, he knows his internet subcultures, his campaign knows how to make things go viral and obliterate his opponent with online owns,” Atkins said.

Don’t expect the posts to stop anytime soon.

Fetterman now says he’ll put up a billboard on the Betsy Ross Bridge connecting the states over the Delaware River that reminds motorists that they are leaving New Jersey for Pennsylvania “just like Dr. Oz.”

___

Follow Marc Levy on Twitter at https://twitter.com/timelywriter.

___

Follow AP for full coverage of the midterms at https://apnews.com/hub/2022-midterm-elections

and on Twitter, https://twitter.com/ap_politics

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.