Demonetized Indians Head for ‘Dangal’

A man poses with replica prints of the demonetized 500 and 1000 rupee notes as part of a street art exhibition in Mumbai, Nov. 20. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced on November 8 that that 500 and 1,000 rupee notes would cease to be legal tender in a crackdown on fraud and tax evasion. The move, which saw the notes withdrawn from circulation just hours after the announcement, was initially welcomed, but frustrations have mounted in the largely cash-reliant country where millions have been left without enough to cover their daily needs. (Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty Images)

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s address to the nation on December 31 eve was an attempt to assuage the hardships of the demonetized common man forced to stand in unending ATM queues over the last few weeks. By all indications, the government should extend more sops in the near future leading to the annual budget and in time for the upcoming elections in Uttar Pradesh, which will surely throw up indicators about people’s thinking about the ban on old notes, writes Siddharth Srivastava. – @Siliconeer #Siliconeer #India #Demonetisation #Demonetization #NaMo #NarendraModi @NaMo @Narendramodi #IndianCurrency #AamirKhan #Dangal

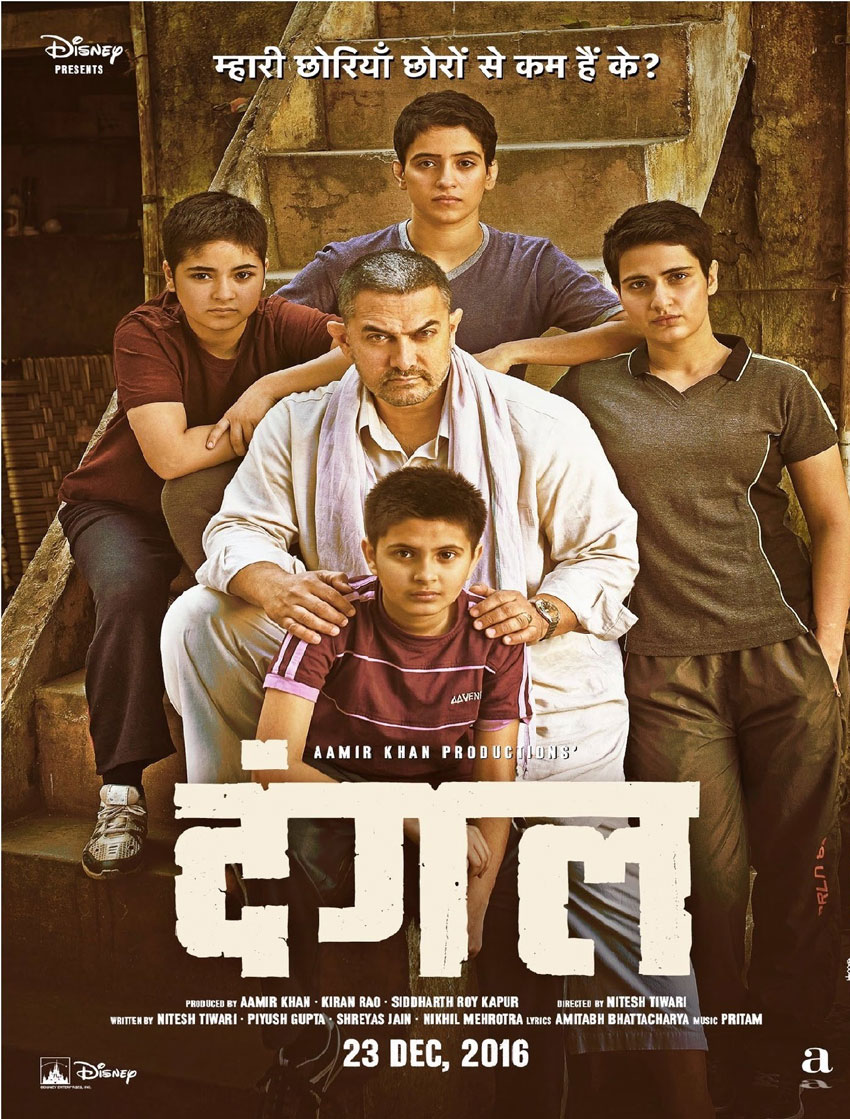

The real succor, however, seems to have arrived from an unexpected front in the form of yet another Aamir Khan-blockbuster, biopic “Dangal,” which, on current trends, is heading towards becoming the biggest grossing Hindi movie of all time.

And this is when movie producers, actors and directors of recent Hindi movie releases are on record to suggest that the November demonetization move of the government has badly impacted business. Cash or no cash, millions from across the country are thronging movie theatres, single screens in rural areas, multiplexes in cities, to watch “Dangal,” to witness the saga of two chirpy young girls making it big in international wrestling, winning medals for India, despite the heavy odds.

The girls have no control over their god-given gender, which makes the fight to the top nearly impossible. They belong to the highly misogynist state Haryana where thousands of females are aborted and do not make it beyond their mother’s womb every year. The sex ratio in Haryana is among the worst in the country, perhaps the world due to a bias against girls who are seen as a burden on the family.

Viewing the struggle of the girls, inflexible patriarchal attitudes and prejudices, jeering relatives and neighbors, fighting stronger boys in wrestling matches, does make the tribulations and discomfort of demonetization, appear a trifling matter. By the time the real medal wining wrestling matches happen in “Dangal,” the audience is well versed with the nuances of the game to be involved in the suspense. This is important as Indians know well the rules of only one sport and that is cricket. The fight sequences and the drama are extremely well shot, with some of the bone crunching bouts, appearing no different from actual action. There is reason that Aamir Khan has earned the label of being the ‘Mr. Perfect of Bollywood.’ His leading role as the ageing, obese father of the two girls Geeta and Babita, the elder two of the famous Phogat sisters of Haryana, is a class act. Aamir has once more successfully moved away from formulaic films that the other two big Khans, Salman and Shah Rukh, have never managed to effectively shed.

What also wins it for “Dangal: is the idiomatic Haryanvi humor that frequently surfaces to keep the audience in splits and breaks the tedium of melodrama and action sequences. For instance, as school kids Geeta and Babita struggle to come to terms with their father’s strictness and regimen when he decides to turn them into champions to fulfill his own dream which was cut short by the need to earn money for his family; the girls’ calculated rebellion that is summarily squashed by Aamir, who does feel the pangs of being father instead of just being the unyielding guru, is particularly endearing. The role of the blundering but good-hearted cousin brother, the punching bag of Geeta and Babita in the early years, is well-etched.

The movie also fleetingly looks at the politics, lack of funds, bureaucratic red tape and bull-headed egoistic coaches and officials appointed by federations.

These are aspects that are very close to reality due to which India continues to be a sporting pygmy except in cricket. It is the individual efforts and sacrifices such as by the Phogat family that have counted and opened the doors for others such as Sakshi Malik, Abhinav Bindra, Sania Nehwal, P.V. Sindhu, Sushil Kumar, who have dared to dream big and gone onto become champions. One intellectual criticism of “Dangal” has been freedom of the girls to make a choice instead of being forced by their relentless father to excel in a field of his choosing. However, such a point of view misses the bigger issue at play here: that, millions of fathers and families in India are not bothered about enabling and investing in the future of their daughters via professional achievement, skills, education and income earning abilities.

The sons, on the other hand, are provided with every opportunity to do so. The mothers educate the girls about household duties, cleaning and cooking; they are married off in early teens, illiterate, unskilled, equipped only to reproduce and serve that leaves them emotionally and physically scarred due to their young age. In many ways, “Dangal” is not just about the struggle of girls in this country. It is the story about millions of boys and girls who do not even get a chance.

It so happens girls outnumber the boys in being neglected, left behind or killed before birth.