DECLASSIFYING NETAJI FILES

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with Surya Kumar Bose, grand nephew of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in Berlin, Apr. 13. (Subhash Chander Malhotra | PTI)

The Central Government of India has yielded to the growing clamor to de-classify files related to the death or disappearance of Subhash Chandra Bose, one of the country’s prominent freedom fighters by instituting an inter-ministerial panel chaired by Cabinet Secretary and attended by officials of Research Wing Analysis, Intelligence Bureau (IB), Union Home Ministry and Prime Minister’s Office to review the Official Secrets Act, writes Priyanka Bhardwaj.

Official records state that Bose had succumbed to burn injuries due to a plane crash in Taiwan on August 18, 1945. His body was cremated and ashes placed at the Renkoji Temple in Tokyo.

However, many of his supporters, descendants and historians do not believe this story and insist that the crash-theory was Bose’s ruse to hoodwink enemies and escape into China or Russia where he could have been eliminated under directions of Stalin.

Working along these suspicions, initially the British intelligence, and then India’s IB maintained a discreet watch over the correspondence, meetings and travels of Bose’s extended family for well over two decades (1948-68).

Almost 41 classified files purportedly contain details of surveillance activities and only in 2007 two of the whole lot could be de-classified by an order of the Central Information Commission.

Finally in 2012, the Home Ministry declassified 10,000 of the estimated 70,000 pages.

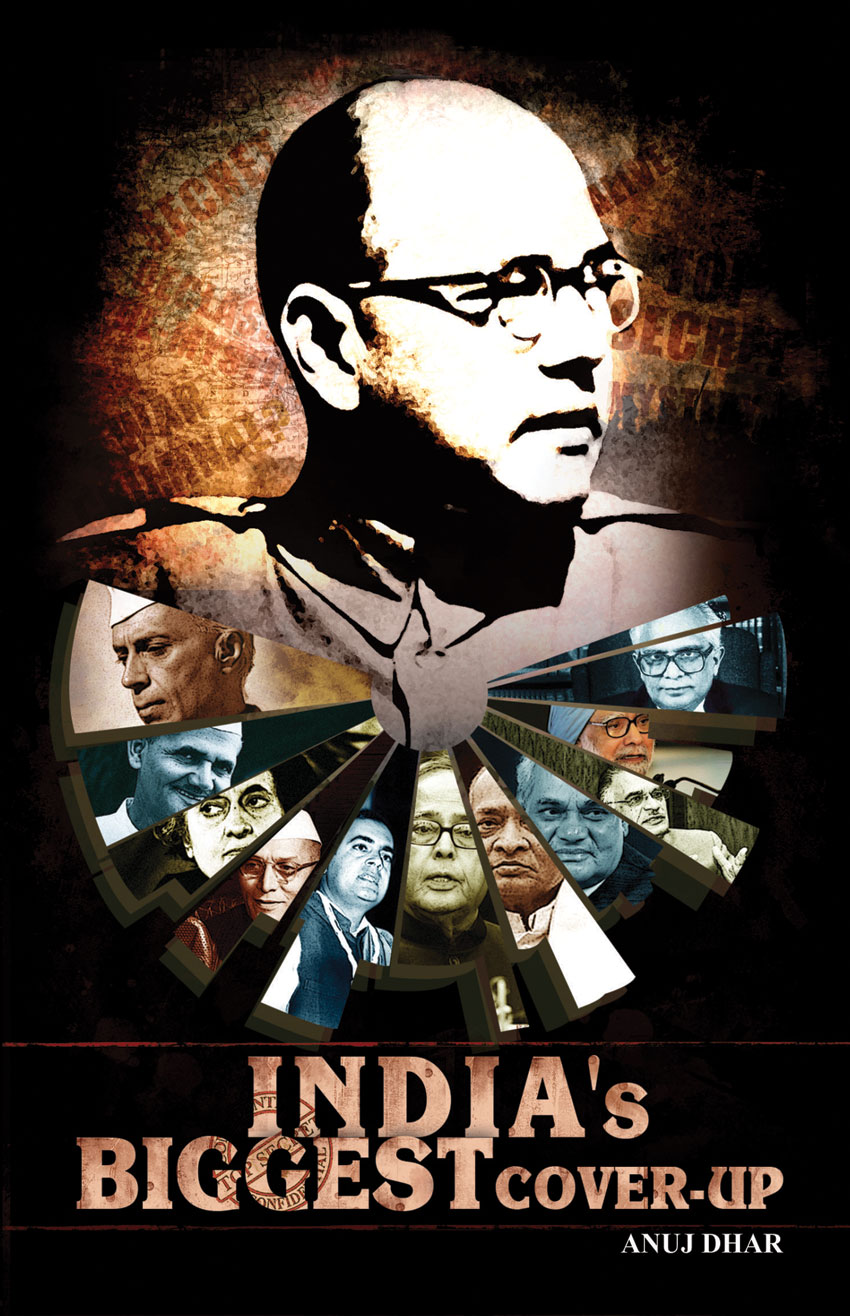

Recently this state directed espionage again made headlines when Anuj Dhar’s book “India’s Biggest Cover-Up” pointedly exposed Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister’s administration of snooping on the kins of Netaji.

Dhar’s 15 years of laborious research of rare Indian and British national archives made him chance upon a particular letter dated November 26, 1957 where Nehru had enquired from India’s the Foreign Secretary, Subimal Dutt, the whereabouts of Amiya Nath Bose, Netaji’s brother Sarat Chandra Bose’s nephew in Tokyo.

It comes to light that to the above enquiry the then India’s Ambassador to Japan, C.S. Jha had assured New Delhi saying, “We have no information about Amiya Bose having indulged in any undesirable activities or expressions of opinion adverse to the Government of India or to its policies. I attach for your information a copy of a news item on him in the Japan Times. As far as we have been able to ascertain, Amiya Bose did not visit Renkoji Temple.”

The leaks, incriminating in nature, have immensely unsettled the oldest national party, Congress that is currently struggling to stay politically relevant.

As a corrective measure the party spokesperson, Abhisehk Singhvi has tried hard to debunk these allegations by drawing attention to the fact that the IB is accountable to the Home Ministry and not the Prime Minister.

Reiterating that the allegations are a “systematic and sinister propaganda of selective leaks and half-truths” he says that these wrongly attempt to tarnish the image of national icons and former home ministers like Vallabhbhai Patel, C. Rajagopalachari, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Govind Ballabh Pant, Gulzarilal Nanda and others.

It is on record that all Congress and BJP governments have been hesitant to declassify all files quoting reasons of internal disturbance and strained relations with certain countries.

However since Independence the “mission-unravel” has reached a point where the Narendra Modi, presiding PM on his latest visit to Berlin promised Bose’s grandnephew and Amiya Bose’s son, Surya Bose, to consider the issue of declassification.

Answering press enquiries Surya Bose responded, “I gave the PM a few points in writing, including the issue of surveillance on the family so that the truth comes out. India as a nation was strong enough to face the truth, even if it was unpalatable. The declassified information needn’t paint a glorious picture of Netaji. It may say something negative. In all probability, it will. We must not shirk from the truth even if it adversely affects Netaji’s image. The family is ready to face it.”

Those in pursuance of clarity on the matter are not ready to accept the findings of first two commissions of inquiry or even the Mukherjee Commission.

It is indeed intriguing to note that Bose’s charisma touched as many people during his short life span of 48 years, as post death!

Born to a lawyer Jankinath Bose in Kolkata, he successfully passed the tough and coveted Indian Civil Services Examination in 1921 only to resign in a year to serve his motherland and fight the British Raj.

It did not take many years for him to become the President of All India Youth Congress, General Secretary and then the Mayor of Kolkata.

Though he harbored no ill will towards Nehru or any contemporary freedom fighters, his style of politics starkly differed with Gandhi’s non-violent freedom movement.

While Bose wanted to build immediate pressure on the British for complete Independence, Gandhi felt the time was not ripe for struggle and relied on compromises with the rulers for attainment of freedom in phases.

In 1939, at the Tripuri session the rift came to the fore when Gandhi chose Nerhu as his political successor and Bose refused to nominate the Congress Working Committee and resigned in protest from the post of President of the party.

Still in quest for freedom for his country, Bose left for Germany in 1941 and then Japan in 1943 to seek help against Britain.

Finally in Singapore he took charge of the Indian National Army formed by Mohan Singh in 1941 from Indian prisoners of war captured by the Japanese.

However the INA was clear that it would pose as any rival center of power to the Congress.

In 1947, when India did become a free nation, the Congress government pleaded for leniency of treatment for the INA soldiers captured by the British by terming them as “patriots albeit misguided” and significant lawyers including Nehru defended INA leaders against court martials in the Red Fort trials.

Yet as destiny would have it, Bose disappeared with the plane crash.

Scholars theorize whether Nehru was impelled to verify Netaji’s demise due to some form of paranoia of an upsurge within the Congress during 1957 or 1962 general elections which could have been mobilized by none other than Bose.

Reasons will be laid threadbare only when the government gives the green signal to disclose all files but till then all and sundry, including readers of this article, will have to suffice with conjectures emanating from dribbles of expose.