China’s OBOR in Way of India’s Sovereignty

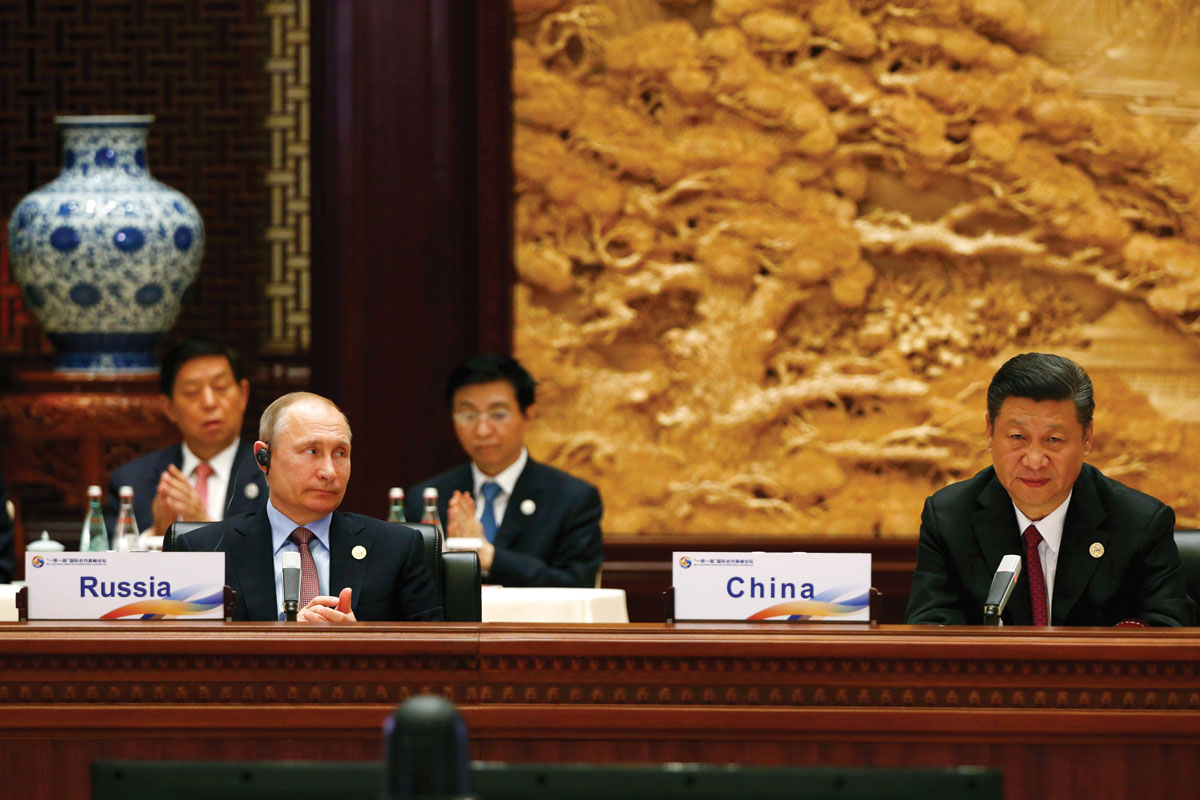

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping (r) attend a summit at the Belt and Road Forum, May 15, in Beijing, China. The Belt and Road Forum focuses on the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) trade initiative. India boycotted the summit. (Thomas Peter – Pool/Getty Images)

China’s vision of Belt Road Initiative (BRI) or One Belt One Road (OBOR), a mega inter-continental connectivity project was boycotted by India as it chose not to attend the conference due to its own concerns, writes Priyanka Bhardwaj.

China held a two day summit between May 14-16 at Beijing to showcase its vision of Belt Road Initiative (BRI) or One Belt One Road (OBOR), a mega inter-continental connectivity project that aims to connect 65 countries and 4.4 billion people in Asian, European and African economies through highways, railroads and maritime infrastructure, trade and investment by way of land-based Silk Road Economic Belt and oceangoing Maritime Silk Road with a total investment of $5 trillion measuring up to 40 percent of global GDP.

Attended by heads of 29 countries such as Russian President Vladimir Putin, Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranil Wickramasinghe, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and several other leaders from U.S., Japan, UK, Germany and France, and heads of UN, World Bank and IMF, India boycotted the conference due to its own concerns.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s appeal that the Chinese have “no political agenda” had not much of an impact on many European countries as they refrained from signing the trade declarations on grounds of absence of consultation process in finalizing it.

OBOR project was initialed in 2013 by Jinping as novel trade stratagems to connect China’s Silk Road Mercantile Belt project in Central Asia with its Maritime Silk Road, through linked bodies of water from the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean that would augment China’s connection with countries along the ancient Silk Road in Eurasia, while creating a new Silk Road across Asia to South Asia and Africa.

Hence, the Chinese enthusiasm to tout the project as a harbinger of peace and stability, strong condemnation of India’s non-participation and even a warning to New Delhi that it can never “impede its neighbors from cooperating” in the infrastructure project.

Till date India has been the most open critical voice against OBOR as the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) that is being implemented without consulting India directly hits at its “sovereign and territorial rights” since the corridor runs through Gilgit and Baltistan in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

Strangely, the $46 billion CPEC links China’s restive Xinjiang region to Gwadar, a southern Pakistani port in the highly restive province that is the stage of an ongoing genocide of the indigenous Baloch people at the hands of Pakistan for fighting for their independence since last 70 years.

If one recalls, soon after becoming President in 2012, Jinping declared that China’s “core interests” will never be sacrificed for the sake of developmental interests as a consequence of which the country’s sovereignty claims over the disputed South China Sea islands has led it to challenge the world.

Therefore, it will be folly for India to forsake its own “core interests” and allow itself to be brainwashed by the Chinese propaganda that the CPEC is only a “commercial” project.

Reports inform that the Chinese have begun to deploy 30,000 “security personnel” to protect the projects along the CPEC route which makes it an active player in the geo-politics of the Indian sub-continent.

That the port will function as a potential future naval post for China is anyone’s guess and with Pakistani and Chinese navies jointly patrolling the Arabian Sea off India’s western seaboard India’s energy and resource supply lines are in danger.

Along with the port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka the Gwadar-Hamabantota axis may become an access denial area in India’s home waters.

As matters stand, the present ruling BJP regime is serious about following their “One China” policy in congruence with China’s “One India” policy unlike the predecessor Congress-led UPA government that was willing to concede Chinese investments in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir in lieu of similar investments in Kashmir.

In this context, it may be worthwhile to bear in mind that time and again and even during Xi’s India visit Chinese troops allegedly crossed the Line of Actual Control that separates India and Beijing put roadblocks to proscribing Jaish-e-Mohammed chief Masood Azhar at the UN Security Council and denying the permanent membership of the Nuclear Suppliers Group to India.

Recently, India’s decision to allow the Dalai Lama to visit Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh had elicited unsavory reactions from the north of the Himalayas.

While India is the second largest contributor to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, it has allocated $100 billion for OBOR and a huge cache for the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor and hence invited India’s criticism.

Another of India’s vital concerns is lack of transparency in conception and financing of Chinese projects and which in the long run could drive smaller economies of south and central Asia and Africa into a trap of “unsustainable debt burden.”

Financial estimate for OBOR is ascribed at about $4 trillion by the Chinese Government, and between $1.6-$1.7 trillion per year on an average till 2030 by McKinsey Global Institute (2016) and the Asian Development Bank (2017).

The latest UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Study (UNESCAP) too reports that the OBOR poses grave social, economic, financial and environmental risks to underdeveloped economies that will receive massive large-scale Chinese investments.

For instance, the China-Uzbekistan investment deal of 2013 is pegged at $15 billion which is equivalent to a quarter of Uzbekistan’s GDP, and the 2014-2015 China-Kazakhstan cooperation agreement valued at $37 billion as well as the $46 billion China-Pakistan 2015 deal are nearly a fifth of the GDP levels of the respective countries.

In India’s immediate neighborhood, Pakistan already owes $62 billion debt to Beijing apart from fresh loans, the 2016 China-Bangladesh agreement equals to 20 percent of Dhaka’s GDP and Sri Lanka too is being lured with an additional $24 billion despite a current debt burden of $8 billion and the Island nation having lost controlling stake in its Chinese developed projects such as the Hambantota Port.

Hence, any slight upheaval in trade balance or balance of payments or debt mismanagement these countries stand a potential of falling into the black hole of debts.

Additionally, there are environmental considerations, genuine transfer of skills and technology to ensure long-term maintenance by local communities, and impacts on natural habitats and indigenous populations.

As development gains have never been universal, equitable or people centric on the social front there is sure shot threat of displacement and marginalization of local communities and indigenous groups as a result of land grabbing and marginalization of workers who are currently employed in industries, abysmal working conditions for migrant workers and construction workers in remote areas that may become obsolete on account of stiff overseas competition, escalating ethnic conflicts and unrest.

The ambitious New Silk Route projects are also an imminent threat to general environmental standards, natural habitats and protected forests that may never be recovered if once lost.

India’s concerns have been appreciated by some neighbors, global agencies and analysts, and as counter projects the U.S. is relooking into two major infrastructure projects in South and Southeast Asia—New Silk Road (NSR) focused on Afghanistan and its neighbors, and the Indo-Pacific Economic Corridor linking South Asia with Southeast Asia—in which India would be a vital player, and talks are going on for similar joint ventures with Europe.

But for harmonious India-China relations Indian PM’s harp on “respect and sensitivity for each other’s core interests” will need to be established by allaying underlying tensions, aggravated by China’s assertive ascendancy in the global order vis-a-vis the West with its vision of OBOR, an infrastructural and territorial manifestation of ‘Pax Sinica’ in keeping with its philosophy of the “Mandate of Heaven” and India’s ideological differences with it in pursuit of fairness, transparency and larger national goals.

The onus to end this impasse may be the Chinese’ but India will need to finesse its relations with China and develop more non-ambivalent ties, wherever possible, to avoid strategic failures.