Brennan Center Outlines 2020 Census Challenges: Misinformation, COVID-19 put People at Risk of Being Overlooked for Next 10 Years

By Mark Hedin, Ethnic Media Services

In June last year, the Supreme Court ended the Trump administration’s plan to ask all 2020 Census respondents about their citizenship status.

But with the first month of census-taking almost complete, it’s clear that the court ruling hasn’t undone the damage caused by even proposing the question be added.

Although the Census Bureau has not yet analyzed 2020’s ethnicity response rates, research two weeks in (https://tinyurl.com/CUNYstudyWeek2), when the national response rate was in the low 40% range, found predominantly Hispanic census tracts were at 30.5%, the lowest of population groups studied. Predominantly African American tracts were at 35%, Asian American-dominated tracts at 41%, and predominantly non-Hispanic white tracts 42.5%.

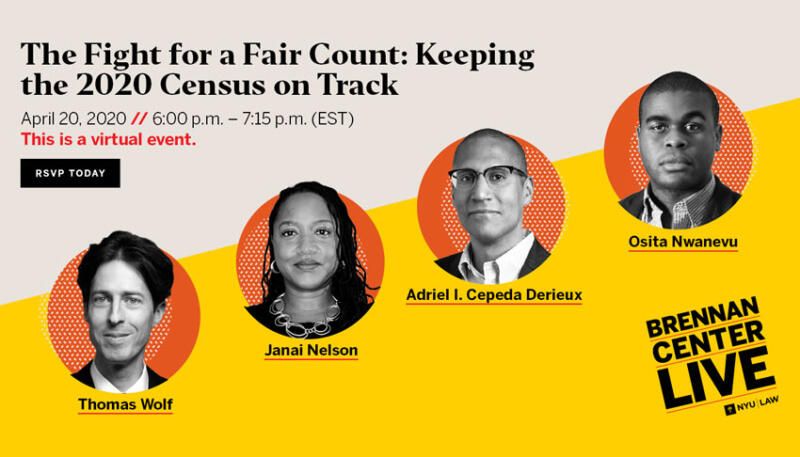

In an April 20 discussion, “The Fight for a Fair Count: Keeping the 2020 Census on Track,” attorney Thomas Wolf of the Brennan Center for Justice’s Democracy Program cited December findings by the Urban Institute (https://tinyurl.com/UrbanInstituteCensusReport) that almost 70% of adult respondents still believed the nine-question 2020 Census form(https://tinyurl.com/QuestionsOn2020Census) would include one about citizenship.

And almost as many expected it “somewhat, extremely or very likely” that authorities would use answers to find people living in the United States without documentation.

The Brennan Center for Justice event also included Janai Nelson from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and Adriel Derieux of the ACLU Voting Rights Project.

The once-every-10-years census controls more than $1.5 trillion of annual federal spending (https://tinyurl.com/CensusDataSpendingReport) and determines people’s voice in government. It does NOT include a question about citizenship or allow police, border or immigration officials, or any other government agencies to use anyone’s personal information from the census.

“That’s a nonexistent threat,” Nelson said. “The larger risk is from not being counted.”

Wolf also cited the report’s findings on how likely people are to fill out the census questionnaire. In 2010, the response rate was 72%. For this census, a majority (77.2%) said they likely would respond, and among those age 50-64, it was 86.9%.

But for those 18-34, it was 67.3%, even worse than the 69.1% of households that include a noncitizen, in which 12% said they definitely or probably would avoid being counted.

Among white non-Hispanics, 81.5% said they were likely to respond. The percentage among those identifying as Hispanic was 71%, among black non-Hispanics 73.3%, and for other races, or those of multiple non-Hispanic ethnicities, 65.6%.

The nation as a whole has now passed the 50% response rate (https://tinyurl.com/CensusBureauReport). That’s about 10% behind where it was at this point in 2010, so the Census Bureau is at least on board to attain what it once deemed its “worst-case scenario” in terms of a low response rate, Wolf said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit 2020 Census plans hard. Plans to reach so-called “hard-to-count” communities have been delayed or altered, and the Census Bureau is also seeking extra time to compile data for use in redrawing political boundaries and reapportioning seats in Congress.

The original deadline for being counted was July 31, but households now have until Oct. 31 to respond online, over the phone, by the traditional method of mailing back a questionnaire, or via an “enumerator” sent to visit those who haven’t responded.

The Census Bureau has also delayed training and deploying the hundreds of thousands of people to whom it offered enumerator jobs. Also, in early March, it suspended after just four days its “Update/Leave” program sending staff to check addresses and leave questionnaires where people are particularly hard to reach, for instance, in tribal lands, or where people rely on Post Office boxes or are dealing with a natural disaster, such as Puerto Rico.

Data the Census Bureau puts together from answered questionnaires determines the need for more than 300 programs that help educate, feed, house, provide infrastructure — and emergency services — for U.S. communities for the next 10 years.

Anonymous census data also is used to redefine a community, city, county or state’s political boundaries. Different states have different procedures on how they go about redistricting. Reapportionment, though, uses census data to decide how many members of Congress each state gets — and the number of electoral college votes in presidential elections.

Each House seat is supposed to represent the same number of people. Currently it is set at 750,000 per seat. After each state gets its one guaranteed House seat, the remaining 385 seats are divided according to population. States the census finds have growing populations gain representatives. States where fewer people are counted will lose seats.

So if people aren’t counted, their communities don’t get a full voice in political discussions.

By 2045, Nelson of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund said the United States is expected to no longer be majority white, but “the popular vote is not reflected in our politics or our representation. All that — political representation — relies on census counts.”

“Encouraging online response is important,” she said. “It’s the same as encouraging voter registration. We need to make sure our friends and family understand. Go into your phones, contact lists, send texts. … Do everything we can to encourage participation while staying safe.”

The census, said ACLU Voting Rights Project’s Derieux, “is the stuff democracy is made of. It can determine what our country looks like. It should reflect the growing diversity of our country.”

“Everyone counts,” Wolf said in conclusion. “When you’re able to stand up and be counted, you have an opportunity to make government the way it should be.”