Big tech data centers spark worry over scarce Western water

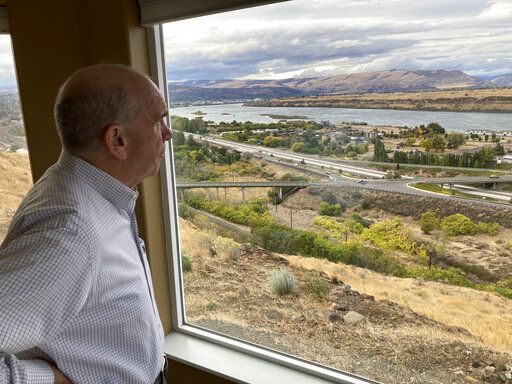

In this Tuesday, Oct. 5, 2021, photo, The Dalles Mayor Richard Mays looks at the view of his town and the Columbia River from his hilltop home in The Dalles, Oregon. Mays helped negotiate a proposal by Google to build new data centers in the town. The data centers require a lot of water to cool their servers, and would use groundwater and surface water, but not any water from the Columbia River. (AP Photo/Andrew Selsky)

THE DALLES, Ore. (AP) — Conflicts over water are as old as history itself, but the massive Google data centers on the edge of this Oregon town on the Columbia River represent an emerging 21st century concern.

Now a critical part of modern computing, data centers help people stream movies on Netflix, conduct transactions on PayPal, post updates on Facebook, store trillions of photos and more. But a single facility can also churn through millions of gallons of water per day to keep hot-running equipment cool.

Google wants to build at least two more data centers in The Dalles, worrying some residents who fear there eventually won’t be enough water for everyone — including for area farms and fruit orchards, which are by far the biggest users.

Across the United States, there has been some mild pushback as tech companies build and expand data centers — conflicts likely to grow as water becomes a more precious resource amid the threat of climate change and as the demand for cloud computing grows. Some tech giants have been using cutting-edge research and development to find less impactful cooling methods, but there are those who say the companies can still do more to be environmentally sustainable.

The concerns are understandable in The Dalles, the seat of Wasco County, which is suffering extreme and exceptional drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. The region last summer endured its hottest days on record, reaching 118 degrees Fahrenheit (48 Celsius) in The Dalles.

The Dalles is adjacent to the the mighty Columbia River, but the new data centers wouldn’t be able to use that water and instead would have to take water from rivers and groundwater that has gone through the city’s water treatment plant.

However, the snowpack in the nearby Cascade Range that feeds the aquifers varies wildly year-to-year and glaciers are melting. Most aquifers in north-central Oregon are declining, according to the U.S. Geological Survey Groundwater Resources Program.

Adding to the unease: The 15,000 town residents don’t know how much water the proposed data centers will use, because Google calls it a trade secret. Even the town councilors, who are scheduled to vote on the proposal on Nov. 8, had to wait until this week to find out.

Dave Anderson, public works director for The Dalles, said Google obtained the rights to 3.9 million gallons of water per day when it purchased land formerly home to an aluminum smelter. Google is requesting less water for the new data centers than that amount and would transfer those rights to the city, Anderson said.

“The city comes out ahead,” he said.

For its part, Google said it’s “committed to the long-term health of the county’s economy and natural resources.”

“We’re excited that we’re continuing conversations with local officials on an agreement that allows us to keep growing while also supporting the community,” Google said, adding that the expansion proposal includes a potential aquifer program to store water and increase supply during drier periods.

The U.S. hosts 30% of the world’s data centers, more than any other country. Some data centers are trying to become more efficient in water consumption, for example by recycling the same water several times through a center before discharging it. Google even uses treated sewage water, instead of using drinking water as many data centers do, to cool its facility in Douglas County, Georgia.

Facebook’s first data center took advantage of the cold high-desert air in Prineville, Oregon, to chill its servers, and went a step further when it built a center in Lulea, Sweden, near the Arctic Circle.

Microsoft even placed a small data center, enclosed in what looks like a giant cigar, on the seafloor off Scotland. After retrieving the barnacle-encrusted container last year after two years, company employees saw improvement in overall reliability because the servers weren’t subjected to temperature fluctuations and corrosion from oxygen and humidity. Team leader Ben Cutler said the experiment shows data centers can be kept cool without tapping freshwater resources.

A study published in May by researchers at Virginia Tech and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory showed one-fifth of data centers rely on water from moderately to highly stressed watersheds.

Tech companies typically consider tax breaks and availability of cheap electricity and land when placing data centers, said study co-author Landon Marston, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech.

They need to consider water impacts more seriously, and put the facilities in regions where they can be better sustained, both for the good of the environment and their own bottom line, Marston said.

“It’s also a risk and resilience issue that data centers and their operators need to face, because the drought that we’re seeing in the West is expected to get worse,” Marston said.

About an hour’s drive east of The Dalles, Amazon is giving back some of the water its massive data centers use. Amazon’s sprawling campuses, spread between Boardman and Umatilla, Oregon, butt up against farmland, a cheese factory and neighborhoods. Like many data centers, they use water primarily in summer, with the servers being air-cooled the rest of the year.

About two-thirds of the water Amazon uses evaporates. The rest is treated and sent to irrigation canals that feed crops and pastures.

Umatilla City Manager Dave Stockdale appreciates that farms and ranches are getting that water, since the main issue the city had as Amazon’s facilities grew was that the city water treatment plant couldn’t have handled the data centers’ discharge.

John DeVoe, executive director of WaterWatch of Oregon, which seeks reform of water laws to protect and restore rivers, criticized it as a “corporate feel good tactic.”

“Does it actually mitigate for any harm of the server farm’s actual use of water on other interests who may also be using the same source water, like the environment, fish and wildlife?” DeVoe said.

Adam Selipsky, CEO of Amazon Web Services, insists that Amazon feels a sense of responsibility for its impacts.

“We have intentionally been very conscious about water usage in any of these projects,” he said, adding that the centers brought economic activity and jobs to the region.

Dawn Rasmussen, who lives on the outskirts of The Dalles, worries that her town is making a mistake in negotiating with Google, likening it to David versus Goliath.

She’s seen the level of her well-water drop year after year and worries sooner or later there won’t be enough for everyone.

“At the end of the day, if there’s not enough water, who’s going to win?” she asked.

___

Follow Andrew Selsky on Twitter at https://twitter.com/andrewselsky

Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.