Google Techie Links Ransomware Attack to North Korea

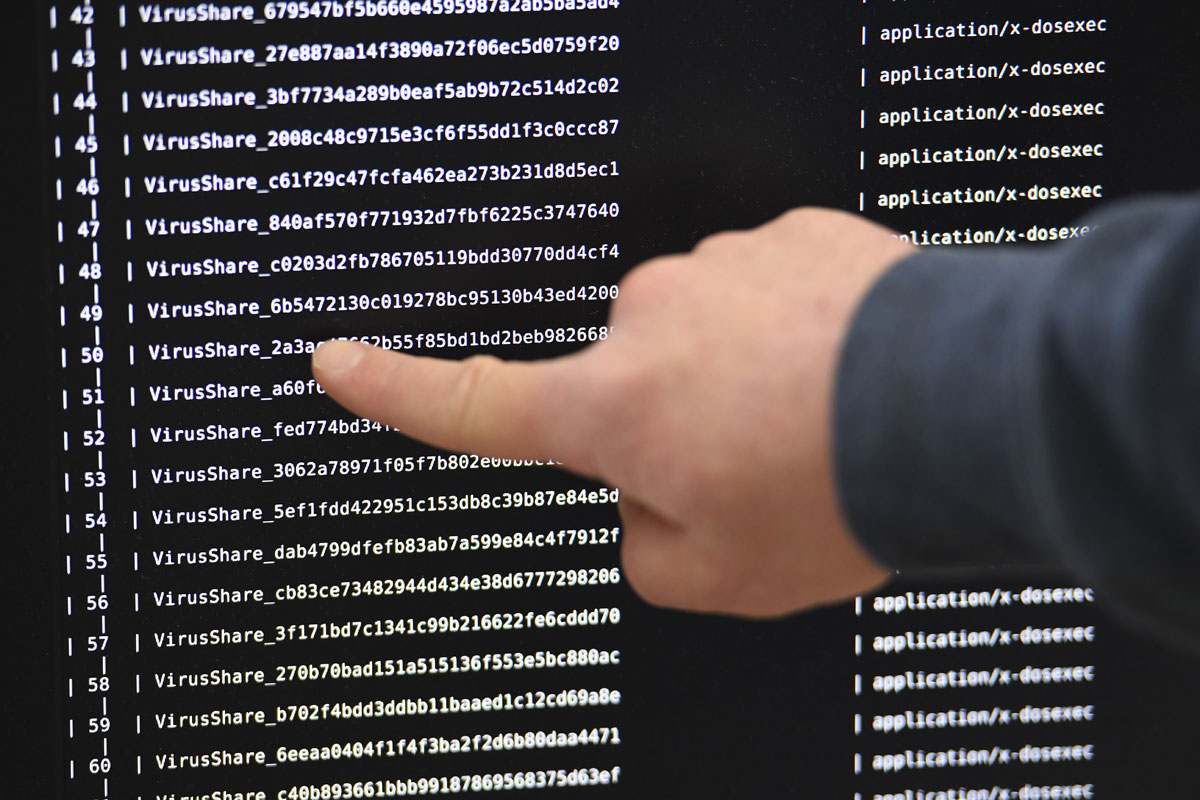

An IT researchers shows on a giant screen a computer infected by a ransomware at the LHS (High Security Laboratory) of the INRIA (National Institute for Research in Computer Science and Automation) in Rennes, on November 3, 2016. (Damien Meyer/AFP/Getty Images)

@Siliconeer #Siliconeer #Ransomware #Google #Tech @Google #TiESV #Indian @TiESV – An Indian-origin security researcher with Google has found evidence suggesting that North Korean hackers may have carried out the unprecedented Ransomware cyberattack that hit over 150 countries, including India.

Neel Mehta has published a code which a Russian security firm has termed as the “most significant clue to date,” BBC reported, May 16.

The code, published on Twitter, is exclusive to North Korean hackers, researchers said.

Researchers have said that some of the code used in the May 12 Ransomware, known as WannaCry software, was nearly identical to the code used by the Lazarus Group, a group of North Korean hackers who used a similar version for the devastating hack of Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2014 and the last year’s hack of Bangladesh Central Bank.

Security experts are now cautiously linking the Lazarus Group to this latest attack after the discovery by Mehta.

Mehta has found similarities between code found within WannaCry and other tools believed to have been created by the Lazarus Group in the past, BBC reported.

Security expert Prof Alan Woodward said that time stamps within the original WannaCry code are set to UTC +9 – China’s time zone – and the text demanding the ransom uses what reads like machine-translated English, but a Chinese segment apparently written by a native speaker, the report said.

“As you can see it is pretty thin and all circumstantial. However, it is worth further investigation,” Woodward said.

“Neel Mehta’s discovery is the most significant clue to date regarding the origins of WannaCry,” said Russian security firm Kaspersky, but noted a lot more information is needed about earlier versions of WannaCry before any firm conclusion can be reached, it reported.

“We believe it is important that other researchers around the world investigate these similarities and attempt to discover more facts about the origin of WannaCry,” it said.

Attributing cyberattacks can be notoriously difficult – often relying on consensus rather than confirmation, the report said.

North Korea has never admitted any involvement in the Sony Pictures hack – and while security researchers, and the U.S. government, have confidence in the theory, neither can rule out the possibility of a false flag, it said.

Skilled hackers may have simply made it look like it had origins in North Korea by using similar techniques.

In the case of WannaCry, it is possible that hackers simply copied code from earlier attacks by the Lazarus Group.

“There’s a lot of ifs in there. It wouldn’t stand up in court as it is. But it’s worth looking deeper, being conscious of confirmation bias now that North Korea has been identified as a possibility,” Woodward said.

It’s the strongest theory yet as to the origin of WannaCry, but there are also details that arguably point away from it being the work of North Korea.

First, China was among the countries worst hit, and not accidentally – the hackers made sure there was a version of the ransom note written in Chinese. It seems unlikely North Korea would want to antagonize its strongest ally. Russia too was badly affected, the report said.

Second, North Korean cyber-attacks have typically been far more targeted, often with a political goal in mind.

In the case of Sony Pictures, hackers sought to prevent the release of The Interview, a film that mocked North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un. WannaCry, in contrast, was wildly indiscriminate – it would infect anything and everything it could, the report said.

Finally, if the plan was simply to make money, it’s been pretty unsuccessful on that front too – only around $60,000 has been paid in ransoms, according to analysis of Bitcoin accounts being used by the criminals.

With more than 200,000 machines infected, it’s a terrible return, the report said.

On May 12, Europol Director Rob Wainwright said, “The global reach is unprecedented. The latest count is over 200,000 victims in at least 150 countries and those victims many of those will be businesses including large corporations.”

The most disruptive attacks were reported in the UK, where hospitals and clinics were forced to turn away patients after losing access to computers.