2 face trial as China enforces online control amid pandemic

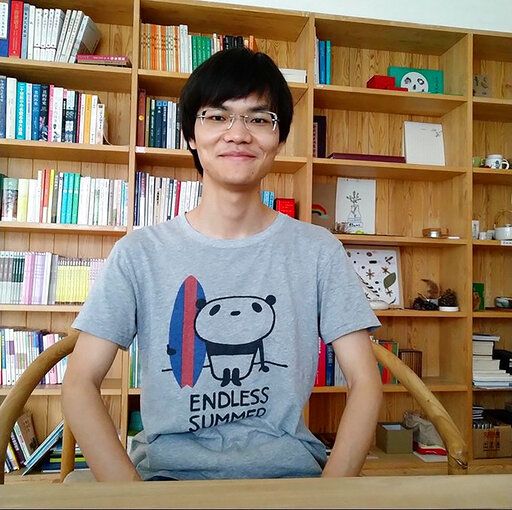

In this photo released by a friend of Cai Wei, Cai Wei poses for a photo in Beijing in June, 2018. More than a year after two young men, including Cai Wei, disappeared from their Beijing homes, they are set to be tried Tuesday, May 11, 2021 in a case that illustrates the Chinese government’s growing online censorship and sensitivity to any criticism of its COVID-19 response. (Friend of Cai Wei via AP)

TAIPEI, Taiwan (AP) — More than a year after two amateur computer coders were taken by police from their Beijing homes, they are set to be tried Tuesday in a case that illustrates the Chinese government’s growing online censorship and heightened sensitivity to any deviation from the official narrative on its COVID-19 response.

Authorities have not said specifically why Chen Mei, 28, and Cai Wei, 27, were arrested in April last year, so friends and relatives can only guess. They believe it was because the two men had set up an online archive to store articles deleted by censors and a related forum where users could skirt real-name registration requirements to chat anonymously.

Started in 2018, the archive kept hundreds of censored articles and the forum saw discussions on sensitive issues including the anti-government protests in Hong Kong and complaints about the ruling Communist Party. But what got them in trouble with authorities appears to be archiving articles showing an alternative to China’s official narrative about its pandemic response just as the country started facing questions over its handling of the initial outbreak.

In keeping the censored articles and providing a place for them to be discussed, the two run afoul of increasingly strict regulations in an already stifling online environment under President Xi Jinping. Just last year hundreds were prosecuted for online speech.

Chen and Cai are being prosecuted under a catch-all charge of “stirring up trouble and picking quarrels.” Chen’s older brother, Chen Kun, said the court appointed lawyer notified family last week that their case would be heard Tuesday.

In January 2020, the two began archiving articles about a mysterious new illness circulating in Wuhan. For Cai, who is from the area and could not go home to see his family for the Lunar New Year holiday, the news was particularly upsetting.

“A lot of things happened in China then that made us very upset, and he may have been affected by that,” said his girlfriend, Tang Hongbo. She was also detained but released after 23 days when it became clear she didn’t know much about the project. “Every day we were looking at the internet, and we were all in this tragic mindset.”

Xi has made cyberspace governance a priority, and under his direction, the government created its own model to manage the challenges and opportunities of the internet. China eliminated online anonymity by requiring people to register under what is known as the real name system starting in 2016. Social media accounts are linked to a mobile phone number, which is tied to an individual’s national ID number.

A Chinese activist, using court and government records and media reports, tallied more than 750 prosecutions for web speech in 2020 in an online database and posted on a Twitter account named SpeechFreedomCN. He said he runs the database anonymously out of fear of retribution.

A friend of Cai, who declined to be named out of fear of retribution, said Cai had grown frustrated with the censorship regime. In response, he and Chen launched the Terminus2049 archive and 2049bbs forum in 2018 as a “public platform of free exchange,” Cai wrote in a welcome post.

“It’s not just the ‘real name’ system — the deletions of posts, the bans, have reached a point that’s really shocking domestically,” Cai wrote in another 2018 post. “When you have to worry about whether you have touched a sensitive keyword in any post you write, how can you really have the brave desire to express yourself?”

On the forum, Cai wrote about movies, music and books he liked. Others discussed mores sensitive topics. It was a place to speak without worrying about having posts deleted or getting one’s account banned. It didn’t require a phone number to register, or even an email address.

Chen was more low-key but similarly chafed against the censorship system.

“He wants information to flow. He wants quality information to flow freely,” said Chen Kun, his older brother. “We have this type of value deep in our bones, the independence of discourse on the internet and the free transmission of information.”

Cai and Chen met in 2011 at a summer camp hosted by Liren College, a socially conscious educational program. Both self-taught coders, they first started cooperating on a project to archive all the lectures and information from the summer camps, said a friend of both, who spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear of retribution. Authorities shut down Liren in 2014.

Terminus2049 primarily housed articles that had been deleted from Wechat and Weibo, popular social media platforms that are subject to regular algorithmic and human censorship. While similar databases existed, most were blocked in China. Terminus2049 was available on Github, a code sharing platform that is not blocked.

The topics the archived articles touched on were broad, but they shared a focus on social issues. One was concerned about the expulsion of migrant workers from Beijing after a fire, while another shared questions about a company that falsified data on rabies vaccines.

It was only after Cai and Chen got arrested that their families found out from friends and peers what the two had been working on. They suspect that pandemic-related content triggered the arrests, in part because in the weeks before and after their detention, police questioned acquaintances about what the two had done during the outbreak.

“They were told that Chen Mei has family members abroad, has provided foreign organizations with information about the pandemic and is basically handing a knife over to the enemy,” said Chen Kun, who now lives in France.

Police in Beijing did not respond to a faxed request for comment and court-appointed lawyers did not respond to phone calls.

Citizen journalist Zhang Zhan also fell afoul of the law after reporting from Wuhan in the early days of the outbreak. She received a four-year sentence in December.

The 2049bbs forum, which never had major reach, is now blocked in China. Yet the discussions continue and the records of the forum live on in a site called 2047, set up by a self-described “person who walks the same path” and some members of the old forum.

Cai’s father, who hasn’t seen his son in more than a year, still can’t understand how his son ran afoul of the authorities.

“He didn’t say anything bad. He didn’t try to organize some protests,” Cai Jianli said. “How did this become picking quarrels and stirring up trouble?’’

Friend of Cai Wei